Bowie's Bookshelf

Why do book lists feel like a bigger deal than other personal lists?

Why does somebody's list of favorite books feel so much more revealing than, say, their favorite movies, albums, or paintings? I'm trying to put aside my English teacher/book blogger perspective on this one, but even so can't help feeling like a books list is a useful measurement for somebody's inner life. I don't mean that this is actually true—but I can't escape the hunch, either.

Let's put it this way: if you were writing a biography of a US President, would you rather have the complete list of movies they watched in the White House screening room, or their personal library with its personal annotations and marginalia? If this seems like an unfair comparison between Reagan and Nixon, consider their favorite books: Nixon was a committed Tolstoyan, while Reagan mostly reached for Tom Clancy potboilers. This feels significant.

This question kept bothering me while I read John O'Connell's Bowie's Bookshelf: The Hundred Books that Changed David Bowie's Life. It's a book-length study, with commentary, on a list that Bowie himself published in 2013. These are, notably, what Bowie called his "most important" books, not his favorites. Bowie loved pulpy science fiction, gangster stories, and Stephen King novels, but his official list was meant to show what works shaped his journey from a nerdy Mod brat to an elder statesman of pop music.

And so, on his list of books, Bowie has the expected books on pop music and culture and edgy literature that an English hipster would enjoy, like Camus or Maldoror, but there are also plenty of esoteric, obscure, and academic works he put on the list: the Gnostic Gospels, The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind, A People's Tragedy: The Russian Revolution 1891 - 1924, which show off Bowie's eclectic intellectual interests. Like most things Bowie did, the list has more than a whiff of self-consciousness to it, especially when you consider that he took the task much more seriously than, say, his attempt to list his favorite records.

That's not to say the book list is a pose. By all accounts, Bowie really was an enthusiastic reader. Even in 1975, at the peak of his “ironic” cocaine fascist period, Bowie was lugging around gilded trunks full of books during his tours or film shoots. When he retired from public life after his 2004 heart attack, friends said that Bowie spent most of his time ensconced in his Manhattan apartment, reading books about Russian history and old English novels. He blurbed books for authors he liked, and for a brief window in the late 1990s, was a walk-on reviewer for Barnes & Noble’s website.

Bowie’s list of important books was an especially suggestive way to explain his own intellectual journey, which O'Connell draws out with a little mini-essay on how each book might have influenced the rockstar. You can see the list for yourself, and read O'Connell's book if you want to know more--it was good light reading for a couple of slow afternoons, and I'd recommend it to Bowie fans.

But I want to focus on why book lists seem so much more powerful than other personal lists. Why is it that, for understanding any public figure who works with their mind, the book list seems to offer more interest and insight than anything else?

1. Books are diverse

One possibility suggests itself immediately: there are so very many kinds of books in the world. Movies have a shorter history, and are exponentially more expensive to make than books, so there are fewer films covering fewer ideas than the printed word. As for music, a subscription to any of the big streaming services will get you many millions of songs covering every conceivable genre from Gregorian chant to Balkan turbofolk, but within this seemingly infinite variety, much of it is generic. I mean that literally: most songs are made to fit a genre, every song sharing rhythms, patterns, and tropes with, quite literally, hundreds of others.

Books are generic, too, but the Dewey Decimal System alone makes room for a thousand categories, with most of those splintering into various subcategories. The engineers at Google Books, back when that company was planning to digitize every individual title in the world, used to throw around the figure of 130 million books. Spotify, by comparison, has about 100 million songs, and many of those are literally noise. Simply put, there are more books than movies or albums, and books on average are more different from each other than other media. A list of favorite books is culled from a larger, more diverse list of options, and so tells us more about the list-maker.

2. Books are made of thoughts & ideas

Another facet of books that most media can't touch: books traffic more directly in ideas. This is obvious when you compare reading to, say, music or painting, which aren't really suited to making arguments, telling long stories, or expressing complex concepts. Movies and television can absolutely work as vehicles for education and communication, but as Neil Postman pointed out, the medium of film tends towards sensation and simplification.

Books, though, are products of pure language, of ideas turned into words, and so come more closely than any other media to resembling the texture of actual thinking. (At least, that’s how it seems to me as a non-specialist: describing music or images in the mind is difficult, but most people readily understand what you mean when you talk about the mind as an inner monologue.) Reading, at least to me, has always imparted the feeling of riding along the grooves of somebody else's mind, and when those grooves belong to a particularly subtle or profound mind, you come away from them feeling smarter than you did a few chapters ago.

3. Books are slow

Last, but maybe most importantly, books are slow. Paperback potboilers off the spinning rack take two or three times as long as the inevitable movie version; even as more novels become TV series rather than movies, as in the case of Game of Thrones, you're looking at a nine-hour show versus a thirty-three hour audiobook. And that's just fiction. When Claud Lanzmann released the full, 9-hour version of Shoah in 1985, it was regarded as pushing the very limits of length for a documentary project. But for any non-fiction book, including thousands of Holocaust histories, nine hours of reading is mid-range, at best. Books take time, and favorite books take a lot of time. Anybody who reads well inevitably reads a lot, and so a list of their important books represents many hours of investment.

4. The meta-book hypothesis

Or maybe—and this is the last point, I swear—there is a sense that I've always had with books, and that many other great readers from Borges to Alberto Manguel to Umberto Eco have intuited, that however many individual books we may read, they are ultimately bound together in the mind as a single, massive, interleaved book of all books. Guy Davenport, who wrote the finest memoir on reading I know of, wrote in "On Reading" that

"The world is a labyrinth in which we keep traversing familiar crossroads we had thought were miles away, but to which we are doomed to backtrack. Every book I have read is in a Borgesian series that began with the orange, black, and mimosa-green cloth-bound Tarzan brought to me as a kindly gift by Mrs. Shiflett in her apron and bonnet."

David Bowie, making sense of a life spent reading, found it important to include his teenage infatuations with Camus and The Beano comics alongside The Visual Arts in Post-Historical Perspective or The Age of American Unreason. Our personal libraries, whether we put them on shelves or carry them around in our heads, mix and intermingle, cross-pollinate, connect. I know of nothing like this with music or movies, despite having plenty of each rattling around in my head. Probably, most people don't feel this way, having filled their heads with more socially-acceptable pastimes like TikTok clips, astrology, or the National Football League. But for us readers, who know the spell of this massive, looping, meta-book, it can be awfully comforting--and revealing--when somebody famous tries to unravel their own endless, spiraling book of books.

From the Archives

If you do enjoy my writing about books and their place in our lives, I did put together a short primer on my own reading habits last year.

How To Read More Books and Why

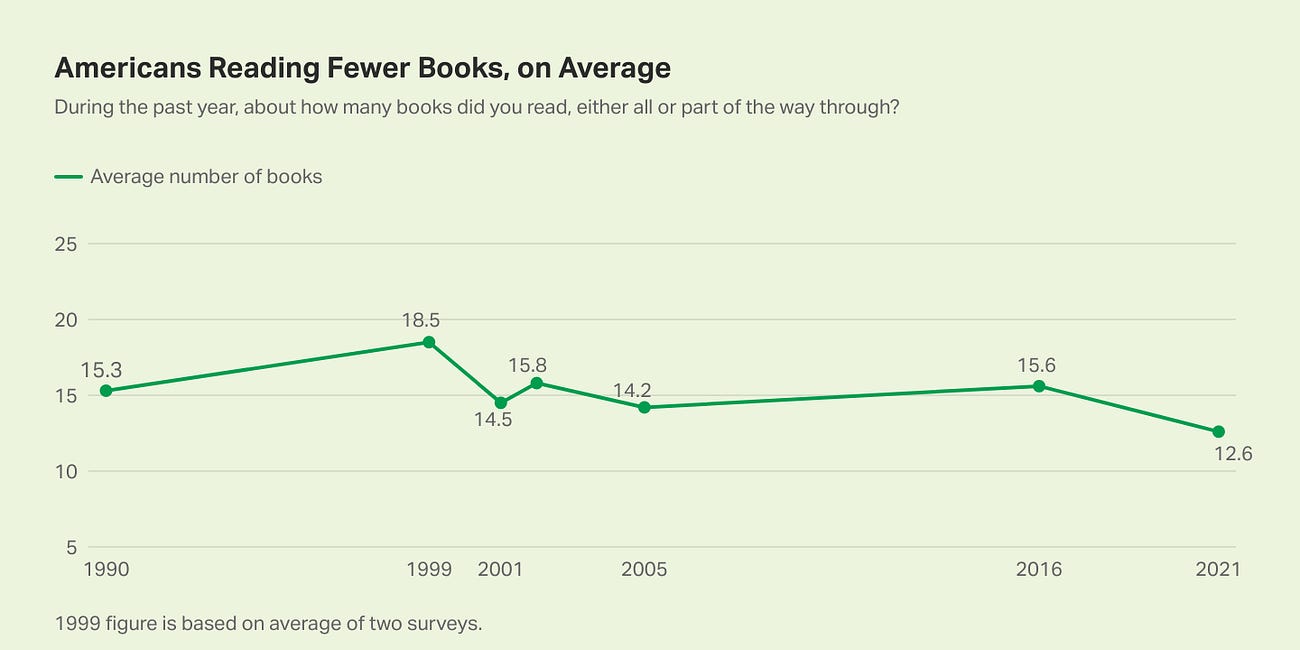

Last week, Gallup released a major survey of American reading habits, and the results don’t look good: between 2016 and 2021, we’ve collectively slid from reading 15.6 books a year to 12.6. The segment of the population that just doesn’t read at all has continued to stay flat around 17% for as long as Gallup has conducted this survey.

Links!

Other things I’ve been reading, in no particular order:

The Pirate Preservationists: how bootlegging movies, music, and literature preserves it from media migration and bitrot

How Emily Wilson Made Homer Modern: I hate the lede, but I adore Wilson’s translation work and will be starting on her new Iliad very soon.

Did New York City Forget to Teach Children How to Read? Moves in the NYC school district have brought the Reading Wars back into discussion again. I’ll be writing about this topic more soon.

Looking at Books3, by the numbers: over at The Atlantic, Alex Reisner has a multi-part investigation of the 193,000 books of the Books3 database, which Meta has admitted to using for training its LLaMa chatbot. This has been enough to incite several lawsuits against Meta by authors who claim this constitutes plagiarism of their work.

Shameless Self-Promotion

I continue to make music with synthesizers in my ever-diminishing free time. I share this with no demands or expectations.

And that’s it for this edition of Musement.

Happy reading!