The Bobs At Work

Or, can you still succeed in publishing just by working hard, writing well, and reading a lot?

Don't get me wrong, I liked Turn Every Page. We bookworms don't get a lot of space in the movies, so it's a pleasant surprise when you hear that somebody is making a documentary about the 50-year working relationship between historian Robert Caro and his editor, Robert Gottlieb. I went to see it last weekend, and I liked it fine. I had some disquieting thoughts about it as a reader. But let's lay out the story first.

You may not know Bob Gottlieb, but you've probably read his work. Among the six hundred or so books that he's edited, you've got all of Joseph Heller and Toni Morrison, most of John Le Carré and Nora Ephron's novels, much of Doris Lessing and Ray Bradbury, and even Michael Crichton in the first decade of his career (which in Crichton time, works out to around thirty-seven books, I think). He was the head of Knopf for decades, and editor-in-chief at The New Yorker. He gets cold-calls from the offices of Bill Clinton and Bill Gates to help him edit their books. Gottlieb has climbed to the peaks of American publishing more often and more readily than anybody else. So you can understand why it's a big deal when he says that the most important work of his seven decades (!) in publishing has been editing Robert Caro.

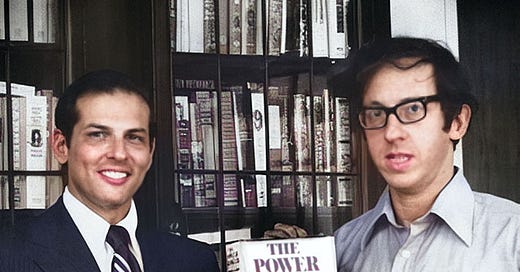

You might know Robert Caro. He spent most of the 1960s either working as a beat reporter or squirreling away time to work on his million-word epic about Robert Moses, New York's legendary city planner. And "epic" really is the right word for The Power Broker: in the documentary, Caro admits that he spent weeks getting the book's opening page exactly right by modeling it on Homer's catalog of ships; another chapter, ostensibly about the Long Island Expressway, devotes several thousand loving words to the geological history of Long Island. The Power Broker came out in 1974, defied all expectations about thousand-page tomes about highway construction by becoming a best-seller, and hasn't been out of print since.

Within a few months of publication, Caro was at work on a biography of Lyndon Johnson, to be published as a trilogy over the course of ten or fifteen years. As of 2023, he is still hard at work on the fifth volume of the trilogy.

And in all this time, Gottlieb has been Caro's editor. Turn Every Page even manages to let us in on an editing session between the two men as, pencils in hand, they work their way through Caro's latest work. If we are lucky and the Bobs are lucky, their fifty-year project may come to a satisfying conclusion before they die.

They are fascinating men. Or rather, their work habits are fascinating: in his memoirs, Gottlieb cheerfully admits to workaholism, reckoning that regular eighteen-hour days at the office aren't a problem if your wife is alright with it and you like what you do. For most of his career, he was able to read several manuscripts a week, considering it rude to leave a prospective writer in the lurch for more than a day or two. Even his hobbies, he admits, aren't fun until they start to feel like work.

Most importantly, he is fastidious. His motto and advice to publishers, repeated in both Avid Reader and Turn Every Page, is "Take every detail seriously." Does that mean, his daughter asks him in the film, that a semicolon is as important as the outline of a first chapter? Gottlieb nods his head: yes, it's possible.

This is why he and Caro have gotten on so well for fifty years. Caro, too, is an obsessive worker. He moves at a glacial pace, yes; but like a glacier, his moves are inevitable, permanent, and awe-inspiring in their scale. Gottlieb recounts a time when, deep into the editing of The Power Broker, he challenged Caro about the accuracy of a reported quote: "I asked myself—and then Bob," Gottlieb writes, "How could he know what had been said between two people, long dead, on the porch of a cabin well over forty years earlier?"

"That's simple," [Caro] said. "When I was studying the Bella Moses archive at Madison House, I came upon a list of campers and staff who were there at the camp during that period, and started to try to track them down." In the current New York phone directory he found a number of names that matched, called them all, and one of them turned out to be the name of the young social worker who had brought the Times to Mr. and Mrs. Moses on that June 1926 morning, and who had overheard—and remembered—Mrs. Moses's comment. What was most extraordinary to me was that when he was recounting all this it was as if this level of research was to be taken for granted—that this is the way every biographer automatically works.

This is why The Years of Lyndon Johnson has taken fifty years to write: Caro goes deep. When he wanted to understand LBJ's childhood, he moved to Texas for three years; when he wanted to learn the truth about the fishy circumstances of Texas's 1948 Senate elections, he tracked down the last surviving members of Johnson's campaign staff; just last year, Caro confirmed that he was finally able to start planning a trip to Hanoi for field research.

And so, despite the dreadful possibility that one or both of the Bobs will die before finishing their great project, Turn Every Page is a happy story: here are two men, both born to Jewish immigrant families in the shadow of the Great Depression, who worked their way to the top of American literature through hard work, attention to detail, and innovative techniques. They seem pretty happy with their lives, families and careers. (Caro can be a bit gloomy at times, but you try staying pleasant when you've spent forty years obsessively studing American politics and the Vietnam War). It is hard to think of a better example of the American dream.

And I guess that's also what made me somewhat sad, watching Turn Every Page. Gottlieb remarks, several times in his memoir, that he is probably the last member of his generation in American publishing still working today. That generation, which got its start in the 1950s and was running much of the show by the 1980s, coincides perfectly with the last high tide for American literature. He was easing into his comfortable emeritus position at Knopf and The New Yorker just as the wolves (corporate acquisitions, mergers, downsizing, computerization) were at the door.

Another way to put it is that it's hard to imagine any head of a large imprint like Simon & Schuster or Knopf confessing to the fact that he never really knew anything about its financial workings or business strategy, and that he never needed to, because he was able to insist on only publishing books that he would personally enjoy reading.

Another way to put it is that Gottlieb got his start in publishing when it was still possible to meet the men whom Simon & Schuster or Knopf were named after, and to get their personal blessings (or at least grudging tolerance) for running the business in his own way, because they held publishing important books and making money in equal esteem.

Another way to put it is that it's really hard, looking at the current the state of publishing and its atrocious burnout rates, to imagine a man supporting his wife and child (with Manhattan rent!) on his entry-level editorial assistant position.

Another way to put it, as Ross Douthat sometimes does, is that Gottlieb's years of peak performance were also the last decades when reading contemporary novels without spaceships or monsters felt like something you were supposed to do if you wanted to be culturally literate.

That's not even getting into Robert Caro, who got his start (and much of his working habits) from old-school gumshoe investigative journalism, a field currently in precipitous decline. He got a huge advance for his financially-risky debut work about toll collecting and bridge construction. Somehow, that book sold well enough for Gottlieb to help secure carte-blanche support for his quixotic LBJ biography, a deal that Caro's own agent admits definitely couldn't happen today. (The publishers originally wanted Caro to do a book on Fiorello LaGuardia, but Gottlieb insisted they give Caro free rein.) For most of his career, Caro has been granted the time, space, and patience to think in terms of years and decades, instead of fiscal quarters and bestseller-list weeks.

To be clear, Caro has done phenomenal work with that freedom, and Gottlieb has done much to advance American letters. I adore the works of both men, and enjoyed celebrating their successes in Turn Every Page. But I wonder, as I watch, if there are simply too many chokepoints in American publishing today—too few jobs, too many naysaying quants, too little in the marketing budget for something ambitious and weird, too much attention lavished in the press on an ever-shrinking, ever-aging aristocracy of Serious Literary Writers.

I wonder if the right people—i.e., not harried English teachers who blog when they should be grading disappointing term papers from the ascendant post-literate generation—will see a movie like Turn Every Page not as a celebration of what has been done, but as a warning about what can no longer be done. I don't really know.

Mostly, I sure hope Caro finishes that goddamned LBJ book.