This essay was originally part of last week’s missive about utilizing ancient Christian attentional practices for pleasure, profit, and reading better. I had to cut it, for two reasons: first, simply for reasons of space and focus, to trim the hedges of an unruly essay; and second, because I found it very difficult to talk about Hugh of Saint-Victor’s little book for building Noah’s Ark without jumping off into wildly different tangents about 12th century theological disputes and virtual reality. It will take some space to connect these dots. Here goes.

One of the challenges facing historian Jamie Kreiner in The Wandering Mind: What Medieval Monks Tell Us About Distraction is that she frequently has to describe the meditative practices of Christian monks to a secular, liberal audience with a narrow definition of the idea. We are used to thinking of meditation as the practice of sitting very quietly, breathing slowly, and trying to empty your mind. This is one form of meditation, one whose cultural transmission has taken a winding, millennia-long road from Nalanda to Chang’an to Kyoto to California to apps on smartphones everywhere. Whether you know it as zazen or dyhana or Headspace.com, this is pretty much the only form of meditation most Americans know. Meditation is the thing where you sit on the floor and stop thinking, right?

Not always, as it turns out. Meditatio has a much older place in Western thought, going back to the earliest Christian monasteries. Unlike the Buddhists with their empty minds, the goal of Christian meditatio was just the opposite: fill your head with as much stuff as possible, then smush it all together into a psycho-spiritual canvas of hyperthinking. Kreiner explains:

For Christian monks, meditation involved a distinctive mix of what scholars today would call directive techniques and thematic structures: their meditations were purposeful and concentrative and worked like their memories did, by association. To meditate on a concept, to think about what something was or meant, a monk searched her memory for something related to it. Then she’d build on that association, and the next, and the next. The goal was a gradual agglomeration of memories that evolved into something much more revealing than any single-sided view could be. It was an exploratory, probing way of thinking. It was a form of prayer but also an act of discovery and creation. It was a means to stretch closer to God, because to think more deeply about the world was to decode the communications that he was constantly sending. It was also a tactic to set the mind in motion without letting it wander aimlessly.

In other words, a monk engaged in meditatio is doing hardcore, highly-structured daydreaming and recall, more Proust than Panchen Lama.

The history of meditatio, or Lectio Divina, as many sources call it, is long and various, taking many forms in western Christianity over the centuries. The basic idea, though, has much in common (and probably is derived from) the older, Classical practice of the method of loci, or “memory palace.” (I’ve written more about this practice in the English Renaissance here.)

Unlike regular memory palaces, though, these meditations were not private exercises, uniquely tuned to the thinker; they were supposed to be shared, replicable spaces that any devout meditator could produce and share. Meditations were virtual spaces, memory palaces that came pre-furnished. But since medieval monks didn’t have Zillow or Minecraft to build these spaces, they had to do it in the sturdiest, most replicable medium of their age: they had to to meditate with books.

Kreiner writes about all kinds of handbooks for lectio divina. There are the riddles of Aldhelm of Malmesbury’s 8th century Ænigmata, “a series of puzzles in which different components of the cosmos—bubbles, ostriches, pillows, constellations—describe themselves by diving past their superficial attributes into more complex ways of seeing.”

There is Hrabanus Maurus’s De rerum naturis, a biblical encyclopedia more than a quarter of a million words in length meant to convey the “inner meaning” (Kreiner) of subjects like “sports, crafts, urban design, domestic space,” and more. “Through Hrabanus’s own meditations,” Kreiner writes, “the text guided its readers to meditate and concentrate on the divine logic that stitched the universe together.”

There is Theophilos of Nubia, who filled every square inch of his cell walls with dense, intricate Coptic texts shaped like manuscript pages, complete with page boundaries and miniature illustrations, with selections including “opening lines from the Gospels, the Nicene creed, lists of saints’ names, stories from the Apophthegmata patrum, and magical texts.” Living inside a giant book, too, was meditatio: “Mural was memory,” Kreiner writes, “Ornamentation was concentration.”

But of all the meditation guides Kreiner mentions, the best of all was Hugh of Saint-Victor’s little handbook of Noah’s Ark. This is a book so wonderfully baffling, a mere description of its contents and usage might be mistaken for a Borges story. In fact, it was a bestseller by 12th century standards, one of the most popular books of its time, with dozens of copies still extant today.

Much of this is due to the author’s popularity. Not much is known about the life of Hugh, except that he was probably German, joined the abbey of Saint-Victor in Paris in the 1120s, and died peacefully in 1141 surrounded by his students and colleagues (I’m depending especially on this book’s introduction, by the marvelously-named Aelred Squire, O.P.).

His works of theology were dense with allusions to philosophy and mysticism, to the rediscovered works of Plato and to the visual arts. Hugh was one of the foremost teachers in the “new theology” movement of the 12th century, as historian Conrad Rudolph puts it in his introduction to De arca Noe mystica, a time when Catholic theology was opening up to influences from pagan Greek philosophy and the liberal arts. This was in direct opposition to the “old” theology of hardcore Biblical exegesis, with no quarter given to pagan idolaters or artisans who thought a stained-glass window could possibly express something of God’s word.

De arca Noe mystica was one of Hugh’s broadsides in this debate, a 42-page lecture given to students to guide their meditations and instruct them using ideas from the new theology. The book guides the reader through an extended tour of Noah’s Ark, filling it with objects meant to educate and enlighten.

But let’s not undersell its grand ambitions: “Very briefly,” Rudolph writes, “the painting of the Mystic Ark portrays all time, all space, all matter, all human history, and all spiritual striving.” By careful study and meditation through the Mystic Ark, Hugh expected to initiate his readers into the secrets of Life, the Universe, and Everything.

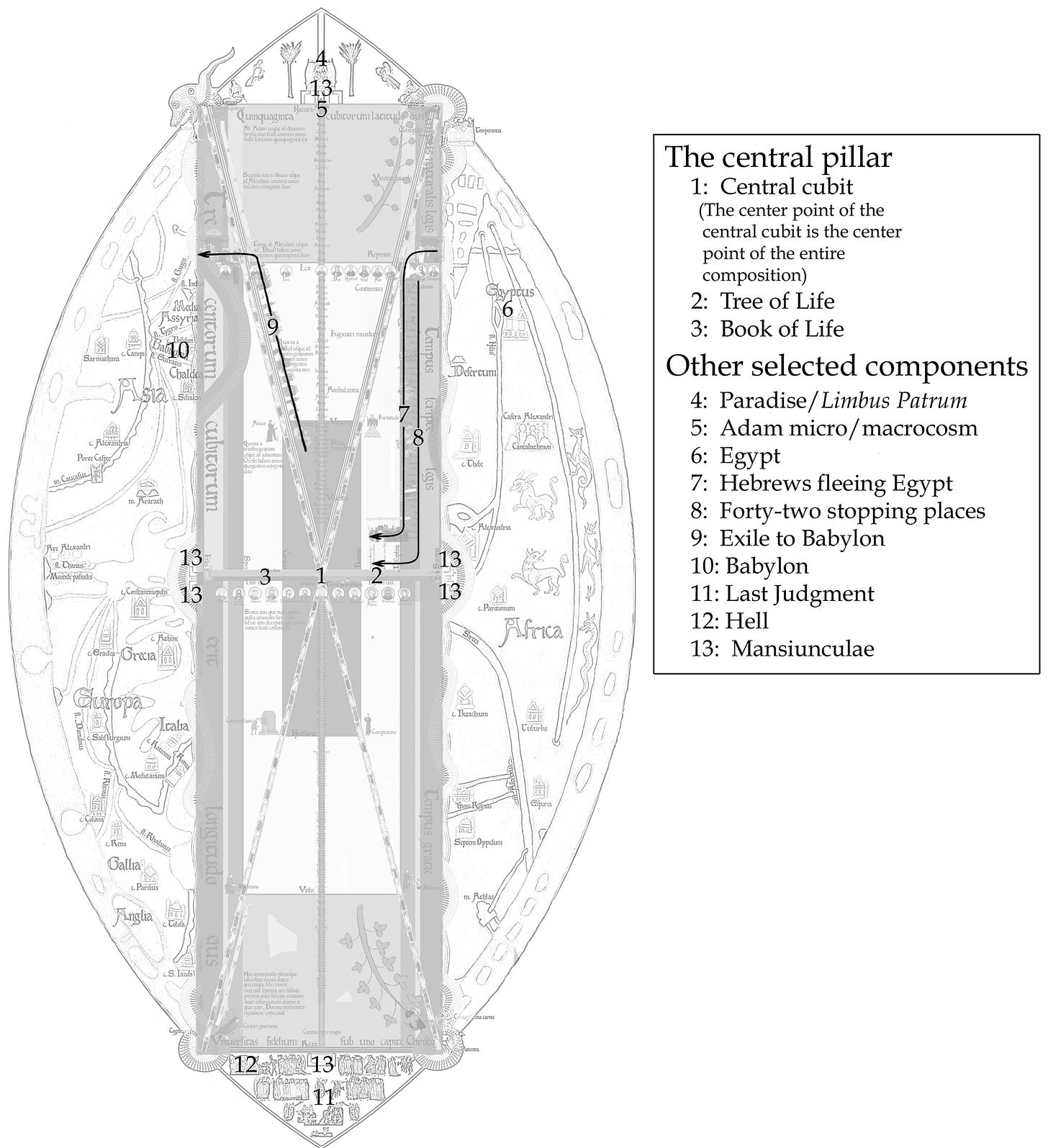

The Mystic Ark, as Hugh describes it, is a kind of memory palace for the universe. Just as the rooms and objects in a memory palace are meant to stand in for some idea, every inch of the Ark is meant to stand in for some crucial concept of theology or the liberal arts. And so, in the very middle of the Ark, for instance, you’re supposed to picture Jesus Christ, a lamb, and the Greek letters for Alpha and Omega, whose collective meaning is easy enough to surmise. For the meditator who has internalized Hugh's Ark, they can walk through it mentally, making startling connections and unexpected discoveries.

Kreiner calls De arca “a virtuosic performance of mnemonic and meditational techniques.” Once a reader has committed the Ark to memory, "he can return to it whenever he wants, viewing it from angles that a painting cannot allow, zooming in or out, outfitting it with new attributes or asking new questions about the features he finds there.” This is starting to sound less like a lecture on theology and more like a video game, or a virtual reality. An enterprising programmer could build Hugh’s Mystic Ark out of pixels and code, seen through VR goggles. Call it the Medieval Metaverse.

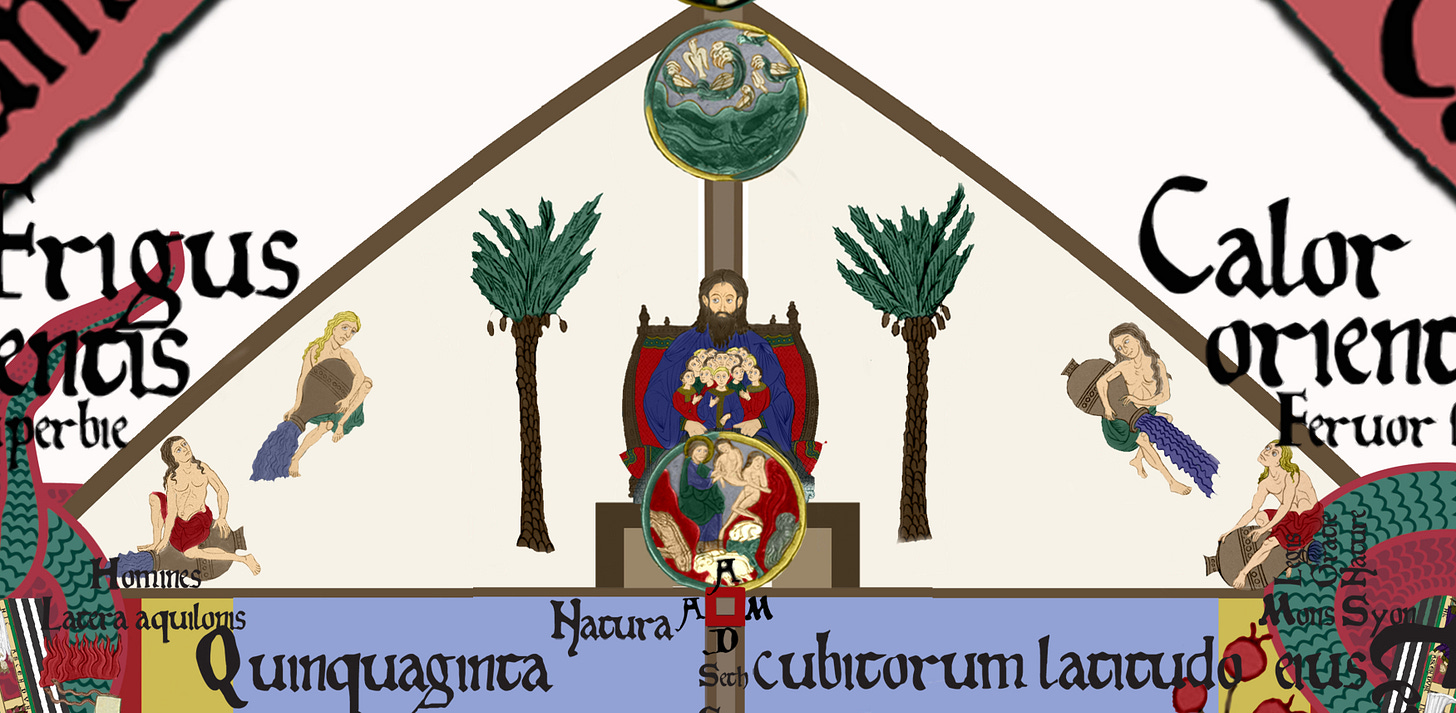

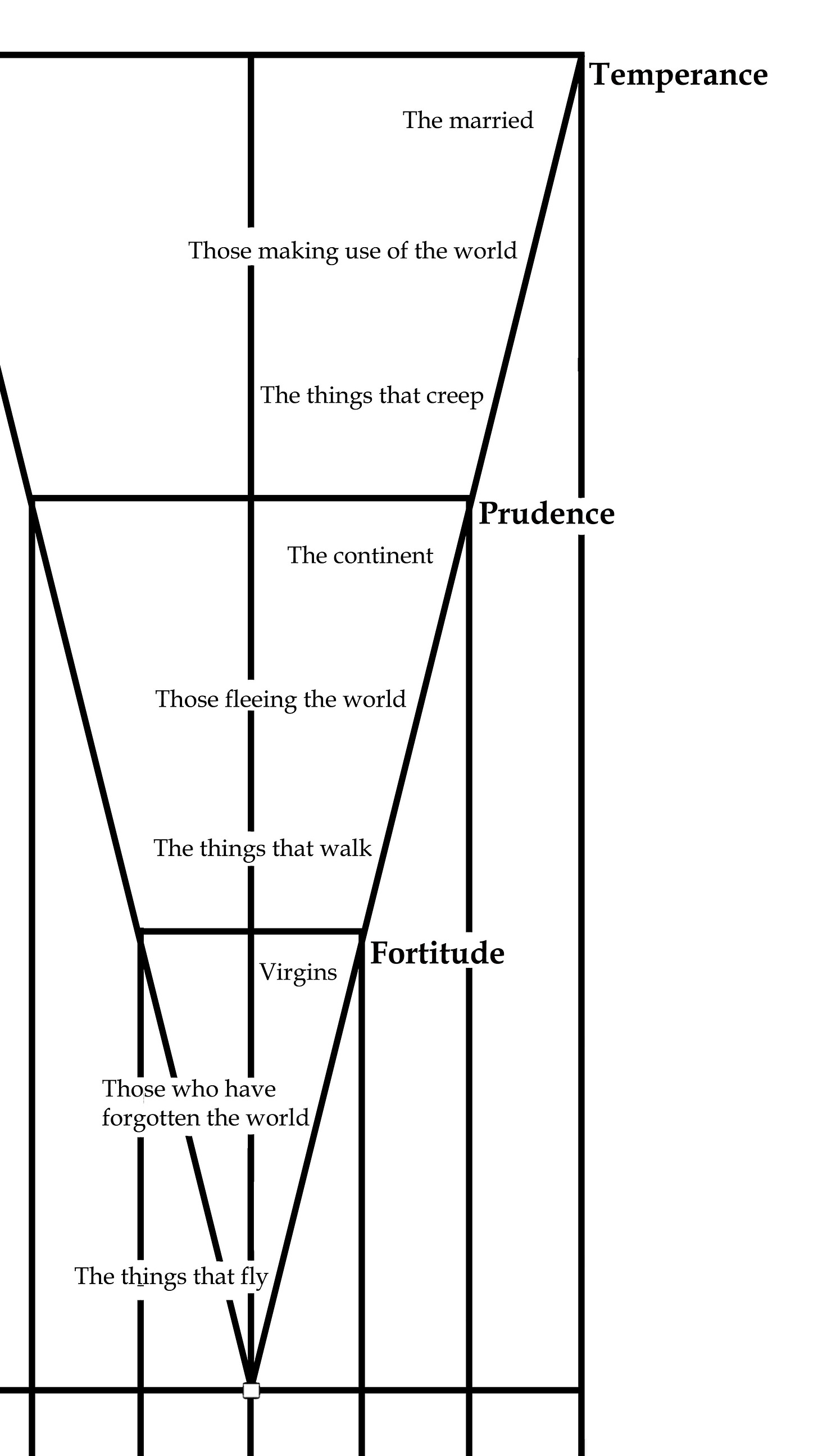

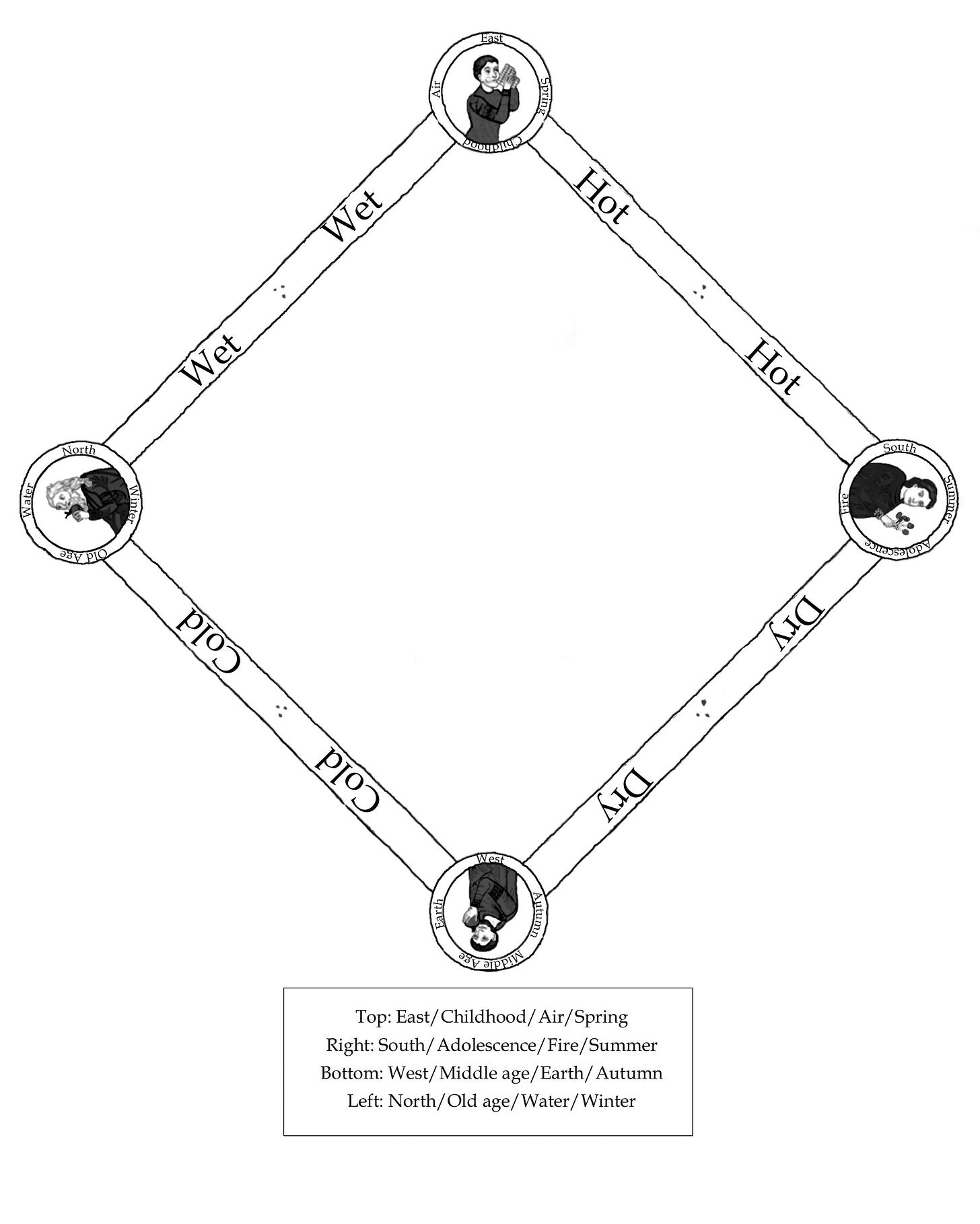

But as you try to read it, things get more complex. There are four ladders on the sides of the Ark, each representing a different path towards God; a walk down the center-line of the Ark is meant to take you through the six ages of Man, from Genesis to the Second Coming; the six days of creation in the Bible are shown emitted from the mouth of God, in a picture of the heavens already choked with complex figures representing the twelve calendar months and twelve more for the signs of the zodiac; oh, and actually, there are four arks, all intersecting in different dimensions, overlaid on top of each other, and overlaid on top of a map of the world, all of it framed by an image of the cosmos. And that’s still not even half of it.

Rudolph, in the introduction to his translation of the text, is skeptical about the feasibility of actually representing Hugh’s meditation: “The text of The Mystic Ark,” he writes, “describes a painting so astonishingly complex that it would be literally impossible to give a description of even the principal figures and their interrelations here, let alone discuss the significance of the work.” After all, despite the book’s massive popularity, we have no evidence that anybody ever actually tried to make the damned painting.

Taken this way, the Mystic Ark might only be a kind of amusing thought exercise, an overheated bit of rhetoric in an argumentative time, or at worst as a kind of monstrously arrogant lecture from a man a bit too taken with his reputation for wisdom. You would have to be a fool, Rudolph thinks, to try and literally represent the Mystic Ark.

Naturally, Rudolph tried to do exactly that. Collaborating with artists and historians, Rudolph’s critical edition of De arca Noe mystica contains an attempt to actually follow Hugh of Saint-Victor’s instructions, using period-appropriate forms and figures. As Rudolph and his publisher have graciously published the images under a Creative Commons license, I have been looting their online gallery for this essay like a gleeful barbarian.

For the record, here’s what Rudolph and his team finally came up with:

By Rudolph’s own admission, if we are to take Hugh seriously, this is only a kind of thumbnail sketch of the Mystic Ark. A real representation would have to incorporate much finer levels of detail in both its map of the world, the four arks, the rooms inside them. To build a true Mystic Ark—and at this point, I’m really convinced that we should—we’re going to need virtual reality. And with all the billions and billions of dollars wasted on building shitty, unpopular metaverse apps, why not make some space in these VR ghost towns for something that will uplift the spirit, herald the infinite glory of God’s cosmos, and serve as the universal key to existence? The regular old metaverses clearly aren’t working, so what do we have to lose?

I eagerly await calls from investors and/or Mark Zuckerberg.

From the Archives

I find myself less impressed with Katherine Rundell’s biography of John Donne than I was when I first reviewed it last year, but I still like my review, which goes a little deeper into how the method of loci was used in the English Renaissance.