The Peasant Humanists of the Italian Renaissance

The Cheese & the Worms & Peasant Reading Cultures

I read all of Sarah Bakewell's Humanly Possible: Seven Hundred Years of Humanist Freethinking, Inquiry, and Hope in a giddy, guilty rush. Giddy, because its gallery of humanist artists, writers, and philosophers was fun company for a couple of long weekend mornings; and guilty, because I hardly needed to read another popular survey of western humanistic philosophy. I have read too many chapters about John Stuart Mill without having ever read any of Mill's own writings. At a certain point, this just becomes a moral failure.

I guess this is my comfort reading zone, scratching the same itch that others treat with formulaic murder mysteries or spy thrillers. The killer will be caught in the end; the good guy will save the world and get the girl; and John T. Scopes will win his right to teach evolution in the state of Tennessee.

But the worst part is, I'm enough of a humanism nerd to have noticed all the strange gaps and elisions that Bakewell makes in her story of secular humanism:

Where are the Epicureans, the Cynics, and the Skeptics? Bakewell's story is centered around humanism as a tradition that emerged with Petrarch in the 14th century, but Petrarch considered himself only the (charming, wise, clever, impossibly handsome) custodian of those ancient philosophies. Epicurus gets a few brief mentions, while the other atheists of antiquity get none at all.

Why, in a book that makes such hay of institutional religion persecuting free inquiry, does the story skip directly from Montaigne at the end of the 16th century to the Parisian philosophes of the 18th? The 17th century is arguably the most important for the story Bakewell wants to tell: halfway between Petrarch's time and ours, it's the century when Descartes made the individual mind the center of selfhood, when Galileo and Robert Hooke made the human eye the ultimate yardstick of nature, and a middle-class butcher's son from Stratford-Upon-Avon introduced a bold, new level of psychological realism to European drama. Isaac Newton's physics, Robert Burton's melancholia, Cavendish's utopian sci-fi, Francis Bacon's experiments, Locke's liberalism, Milton's Aeropagitica—and so much of that unfolding under Puritan rule! It felt as though a chapter had been ripped out of the book.

This might be my own experience in the trenches of recent decades in atheism, but Bakewell skips through the early 21st century with only a few glancing comments on blasphemy laws and right-wing nationalism. But I was there (I know, I know), and I remember those years being much more preoccupied with religious fundamentalism: Kansas and Kandahar, basically. Bakewell doesn't mention two of the most important, anguished breakthroughs in humanism of those years: that humanists can say all the right things and still be catastrophically wrong (Hitchens, on the War on Terror), and that humanists can say things that are perfectly true while still being a massive tool (Richard Dawkins).

The most glaring omission, though, actually comes near the beginning. As is standard in triumphalist histories of humanist philosophers (again, I've read a few of these books over the years), Bakewell has to begin with the necessary caveat that we're mostly going to be joining her for a celebratory tour of aristocratic European men, and that most of them depended for their leisure time on various mixtures of serfdom, slavery, patriarchy, and colonialism. That's all fine and necessary.

But the thing is, I'd also just read a book about peasant humanists in Renaissance Italy. There were actually quite a few of them, and their stories have barely been told. There are many, many books like Humanly Possible. There are almost none like Carlo Ginzburg's The Cheese and the Worms: The Cosmos of a Sixteenth-Century Miller.

The book is a "microhistory"—Ginzburg's own term for the kind of histories he started writing in the 1970s, which center on a single primary source, read it microscopically, and place its meaning in context with wider historical events. This just sounds like "doing history" today, which only underscores how inundated European universities were with sweeping, generalized Marxist historians. At least, that's the impression I got from Ginzburg's combative introduction to his methods.

In The Cheese and the Worms, that micro-source is a set of court transcripts for the trial of an accused heretic from rural Italy in the late 16th century. And though he was tortured and executed for claiming, among other things, that God was like a worm and the universe was like a wheel of cheese, he also sounded an awful lot like a classical humanist.

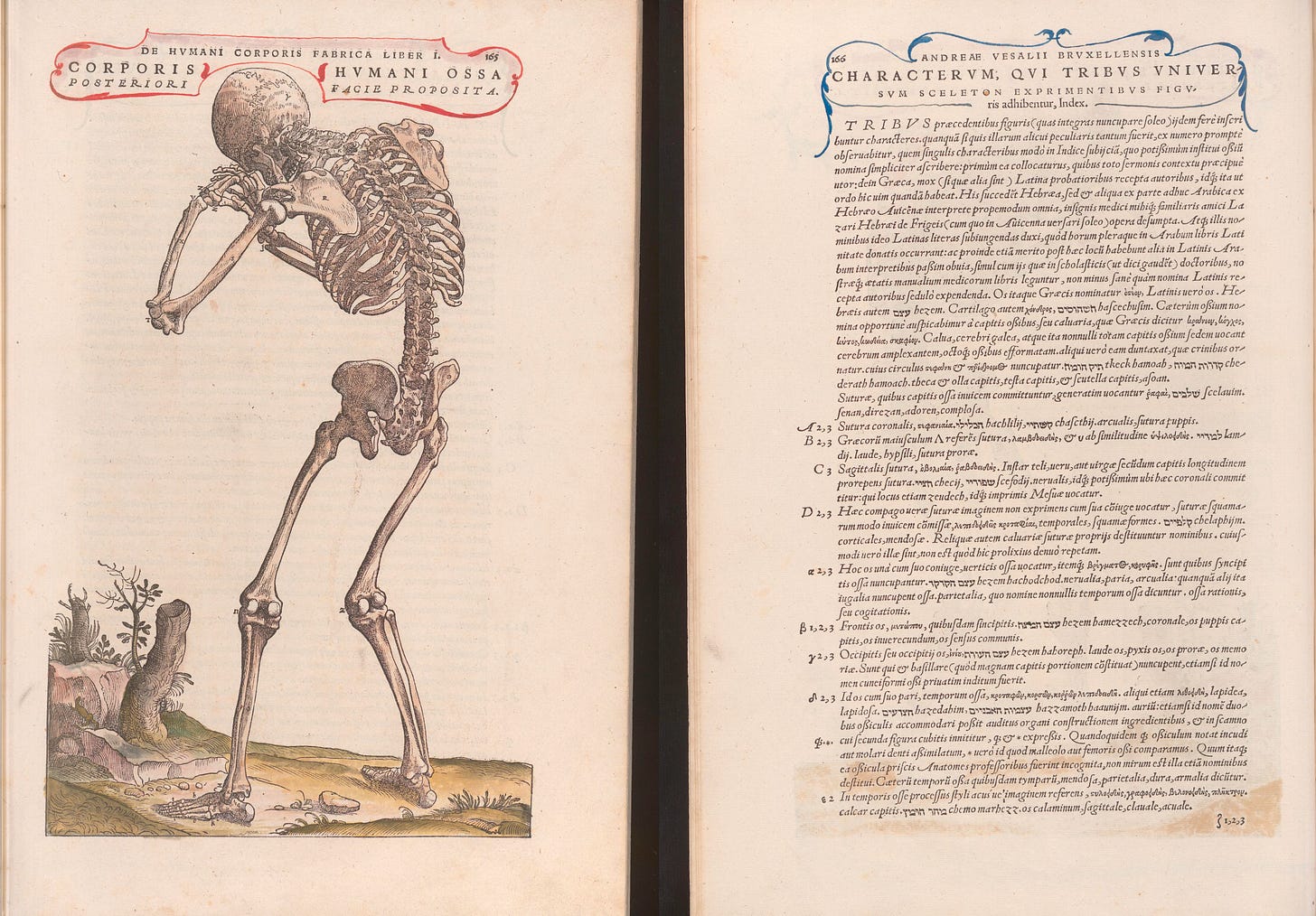

Menocchio was a miller from Friuli. At some point in his life—he was already fifty when he appears in the historical record—Menocchio had learned how to read. This by itself is less surprising than mainstream history often makes out: Ginzburg describes several schools operating in villages and towns across northern Italy at the time, open to the children of citizens. Printing presses were everywhere, and books were available, if expensive, for well-off villagers like Menocchio. "Books," writes Ginzburg, "were part of daily life for these people. They were objects to be used, treated without excessive regard, sometimes exposed to the dangers of water and tearing."

However, Menocchio's particular collection of books was unusual. We can guess as much because the Church, at his trial, felt compelled to list them. Among them were a vernacular Italian bible, a collection of apocryphal gospels, The Golden Legend, The History of the Jews, The Decameron, the marvelous and surprising travels of Il Cavallier Zuanne de Mandavilla through the Holy Land, and an unidentified book alleged by one witness to be an Italian translation of the Qur'an. (Though nothing in Menocchio's testimony supports this claim.)

Having little in the way of a formal education or contact with the intellectual community of his time, Menocchio read his books in his own way, memorizing large chunks of the text and spinning out bizarre theories by drawing connections between the disparate sources. Despite his literacy, he was a product of an oral culture. Ginzburg writes:

When we compare, one by one, passages from the books mentioned by Menocchio with the conclusions that he drew from them (if not with the manner in which he reported them to the judges), we invariably find gaps and discrepancies of serious proportions. Any attempt to consider these books as "sources" in the mechanical sense of the term collapses before the aggressive originality of Menocchio's reading. More than the text, then, what is important is the key to his reading, a screen that he unconsciously placed between himself and the printed page: a filter that emphasized certain words while obscuring others, that stretched the meaning of a word, taking it out of its context, that acted on Menocchio's memory and distorted the very words of the text.

And from this eclectic personal library, stewing in his parochial mind for years, Menocchio had come to a startling realization: the Catholic Church was wrong. Mary was not a Virgin; Christ had not been crucified, nor resurrected; and "Priests," he said, "want us under their thumb, just to keep us quiet, while they have a good time." Muslims and Jews were not evil infidels, he said, but fellow children of God who had been entrusted by the Lord to practice their own faiths. The universe, he said, was not created by God; God was created by the universe. The miller's cosmology requires quoting in full:

"I have said that, in my opinion, all was chaos, that is, earth, air, water, and fire were mixed together; and out of that bulk a mass formed - just as cheese is made out of milk—and worms appeared in it, and these were the angels. The most holy majesty decreed that these should be God and the angels, and among that number of angels, there was also God, he too having been created out of that mass at the same time, and he was made lord, with four captains, Lucifer, Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael.

It's not fair, as capsule summaries of Menocchio often say, that he actually thought the universe was made of cheese. It was like cheese, in that it went from a chaotic slurry to an ordered structure, and that it spontaneously generated life just as cheese was thought to generate worms. God, in this metaphor, was created by the cosmos, not the other way around, and He had to follow its laws. In other words, the miller of Friuli had home-brewed his own deism.

He was warned, repeatedly, by friends and the village priest, that these ideas were heresies, but Menocchio persisted. "Everybody has his calling," he said: "some to plow, some to hoe, and I have mine, which is to blaspheme." He persisted, and the Inquisition was called.

At trial, which was fully transcribed, Menocchio alternates between contrition and lunatic courage, proudly arguing his chaos-cheese Genesis with the learned men of Rome. Nobody was convinced. After many long days of interrogation and interrogation, Menocchio recanted. He was declared a heretic for his ideas and a heresiarch for trying to teach them. The Inquisition locked him in prison for two years, then sent him home.

But even weakened, impoverished, and shamed, Menocchio held on to his beliefs. A decade after his release from prison, the Inquisition caught wind of a Friulian peasant who had asked if Turks were really infidels just for professing the faith of their fathers. Menocchio was arrested again; was found guilty, again; and was condemned to death. His official cause of death was not recorded, though he was most likely burned at the stake.

Menocchio's crimes were, ultimately, to question the authority of the Church, relying on his own intuitions, lived experience, and eclectic personal library. He defended his ideas in court. He spread knowledge by teaching his fellow villagers to read, and showed an inexhaustible curiosity about the world beyond the hills of Friuli. Deism, anticlericalism, toleration, education: Italian humanism was alive in this self-taught bumpkin, who risked—and lost—more than anyone in Bakewell's gallery of elite intellectuals.

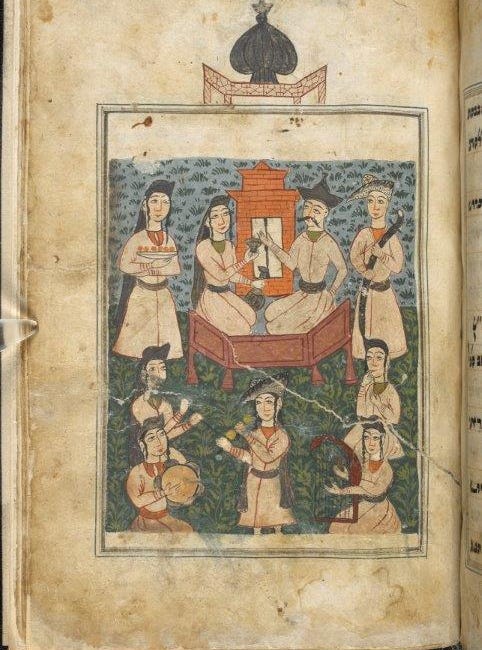

And Menocchio wasn't alone, either: Ginzburg finds traces, in the Inquisition's records, of other village heretics: Fra Giovanni Melchiori of Polcenigo, who was censored for voicing his private theology of Judgment Day; another miller, Pellegrino "Pighino" Baroni, was arrested a few years before Menocchio for denying the authority of the Catholic Church; and most astonishingly, there is the pseudonymous folk poet Scolio, who wrote a lengthy poem describing divine visions granted to him by the angels. The Settenario, which has never been translated into English, describes how all the religions of the world are really one, sharing in the same holy wisdom, and that only priests and princes are keeping the peasants of the world from achieving universal brotherhood and cornucopian abundance.

There's almost nothing about Scolio that I can find in English except for his few mentions in The Cheese and the Worms, but in Ginzburg's telling it was a popular poem in its time, a bridge between the earlier peasant dreams of Cockaigne with idealistic, philosophical utopias that were so popular with humanists. It's likely Menocchio knew about it. It's also likely that many Italian villages had their own Menocchios, or Pighinos, or Scolios expressing, in their rustic dialects, many of the same ideas that wealthy urbanites had typeset in Latin. And this is a much more fascinating story than hearing, yet again, about Montaigne's Latin lessons.

Of course, this kind of history is hard. It's hard to write, because you have few secondary sources to do the summarizing for you, and must instead comb through the dust-dry archives of the Inquisition for rare glimpses, beyond all the torture and bureaucratic Latin, of genuine human expression. And it's hard to read, because you can't fall back on three or four other books you've already read, or some broader cultural narrative to shepherd you through the story. But you do learn a lot when you put down the guilty pleasures and read something new.

From the Archives

A few months ago I wrote about another idiosyncratic reader of the vernacular Bible, and how it led to the creation of the Ultra-Orthodox Jewish community of the Amazon rainforest:

The Peoples of the Post

On a winding road outside the village of Milpoc in November 1944, Segundo Eloy Villanueva’s father was murdered. His body was found slumped by a tree, with a bullet in his chest, his face disfigured by knife wounds, and a coin left in his mouth. The murder was no mystery: Villanueva had been arguing with his neighbor Filadelfio Chávez for months, and o…

Links

In no particular order, a few readings I’ve enjoyed since the last dispatch:

A Writer Attends the Frankfurt Book Fair. Read, and despair. Pairs well with 10 Awful Truths About Book Publishing.

The Pirate Preservationists who are keeping media alive (sometimes accidentally) in the capricious era of streaming.

How English Became a South Asian Literary Language. The obvious answer is “colonialism,” but the longer answer is fascinating.

Where Do Fonts Come From? Not, like, historically, but new fonts, available for purchase online. I had heard troubling reports about Monotype, but nothing this bad. Bust the font monopoly!

The Book Blurb Problem Keeps Getting Worse. Notice how the title (correctly) assumes blurbs were already a problem.

The Strange, Secretive World of North Korean Science Fiction.

And that’s all for this week. The return of the school year has me very busy, but I hope to return with another essay before the end of September.

Happy reading!