December Links

Deaths in 2022, the public domain in 2023, and people pretending to be robots pretending to be people

Sic transit annus MMXXII.1

Here’s some of the best writing on writing and reading about reading I found in December. All links to images are embedded in the images themselves if you want sources.

Literary Deaths of 2022

Bill Morris over at The Millions has put together a good list for deaths in the world of letters this year. Besides Hillary Mantel and Javier Marías seem like the big ones here: both were already quite old, but as they were still lucid and productive, it feels as though we were robbed of a few more good books. Morris focuses on some of the less-famous names, many of which I was grateful to hear about and are now on my radar.

King Xavier Marías

Marías’s death is especially bad news for the Kingdom of Redonda, where he had ruled as as King Xavier since the early 1990s. Yes, really. Sort of. The Times Literary Supplement has it covered in its review of Michael Hingston’s Try Not To Be Strange, the history of Redonda. Legally, Redonda is just a tiny desert island off the coast of Antigua.

But according to an elaborate legal fiction dating back to 1865, Redonda is an independent country with its own monarch and royal court, which consists entirely of famous writers and artists. J.M. Coetzee, Alice Munro, and Umberto Eco are peers of the realm. Javier Marías was its king, a title that he took seriously, if not literally. For a while, though, there were pretenders to the throne, the dispute dating back to when King Juan I (English writer John Gawsworth) sold his title to cover his bar tab. But overall, the reign of Xavier I was a peaceful and prosperous time for the fictional kingdom.

As of press time, no successor has emerged following the death of the king.

How Barnes & Noble Got Its Groove Back

Barnes & Noble was the poster child for big-box corporate failure in the 2010s. As Amazon and other online companies continued to grow explosively, B&N floundered about, experimenting with poorly-supported e-readers and selling literary tchotchkes like Harry Potter socks. In a particular low point, they tried opening a restaurant chain. None of it worked.

But the decline reversed in 2019. Sales at B&N are growing again, dozens of new stores were opened last year, and 2023 is poised to be the company’s biggest year in a long time. What changed? I’ll leave it to Ted Gioia, Harvard MBA, former McKinsey consultant, and international man of jazz mystery, who breaks it down over at his Substack. The short version: James Daunt, the new CEO who replaced the creepy, incompetent old one, actually likes bookstores. So he went about giving his employees and local managers more autonomy to sell the books they wanted to sell, eased off the pre-inked display deals with publishers to increase trust between buyer and seller. Wouldn’t it be nice if every major corporation was run by somebody who actually knew and enjoy their products and services?

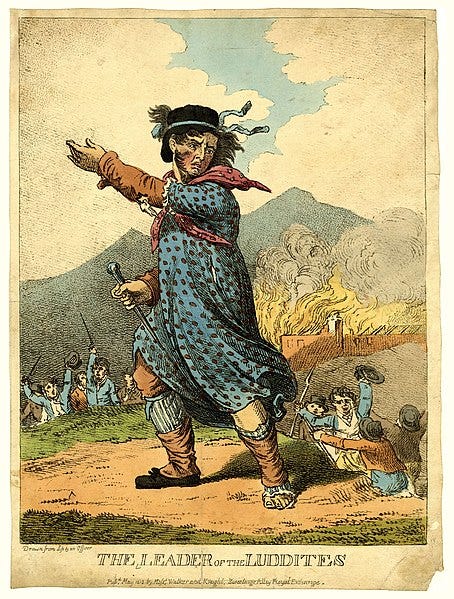

Teenage Luddites

The amount of time American teenagers spend on their smartphones is horrifying. Everybody knows this, including the teenagers. I see it every day as a teacher. So I was enormously heartened to read about these teenage luddites in New York deleting their accounts and putting away their smartphones. They’re rebelling against the system by going to the library!

For the first time, [Logan] experienced life in the city as a teenager without an iPhone. She borrowed novels from the library and read them alone in the park. She started admiring graffiti when she rode the subway, then fell in with some teens who taught her how to spray-paint in a freight train yard in Queens. And she began waking up without an alarm clock at 7 a.m., no longer falling asleep to the glow of her phone at midnight. Once, as she later wrote in a text titled the “Luddite Manifesto,” she fantasized about tossing her iPhone into the Gowanus Canal.

These kids are alright. With any luck, we’ll have a genuine counterculture again thanks to teens like this.

Thomas Pynchon’s Work Books & Books in Thomas Pynchon’s Works

Speaking of luddites, one author who still somehow isn’t dead is Thomas Ruggles Pynchon. Now 85 and presumably retired, Pynchon has donated his entire collection of writings, comprising novel drafts, correspondence, research, and more, to the Huntington Library in Los Angeles. That’s 70 linear feet of shelf space in all. To put it in concrete terms, that’s about as much shelf space as two and a half Thomas Pynchon novels.

The news pairs well with Alan Jacobs releasing an outstanding Pynchon primer gratis on his blog. The discussion at the end, about the lowly status of books and reading in Pynchon’s works, was especially illuminating:

Pynchon writes long, complex, demanding, learned books about people who don’t read long, complex, demanding, learned books, and while this could be said of many other writers as well, in Pynchon it has, I think, a particular significance. Almost all of Pynchon’s characters are caught up in immensely complex semiotic fields. All around them events are happening that seem not just to be but to mean, but the characters lack the key to unlock those mysteries, and as they try to make their way are constantly buffeted by the sounds and images from movies, TV shows, TV commercials, popular songs, brands of clothing, architectural styles, particular makes of automobile … all combining to weave an almost impossibly intricate web of signification. Rare indeed is the Pynchonian character who is not entangled to some degree in this web.

By doing what he does in book after book, Pynchon clearly indicates not just that he finds this entanglement problematic in multiple ways — psychologically, socially, politically — but also that the primary means by which the entanglement may be described and diagnosed is that of books — large books comprised of dense and complicated sentences. In Pynchon’s fiction we see an immensely bookish mind representing an unbooked world, and its great unspoken message is: Let the non-reader beware.

I like this interpretation. The usual Pynchon protagonist is smart but rarely wise, lacking the patience to understand the weird forces at working obscurely against them. Anyway, I need to re-read all my old Pynchons.

The Public Domain Class of 2023

One of the fun little things that comes with every turning of the calendar is the new class of works entering the public domain. Now we’re up to the class of 2023/1927. Duke Law’s Center for the Study of the Public Domain compiles a great list of the best new entries. The standouts this year are:

Metropolis, directed by Fritz Lang

To the Lighthouse, by Virginia Woolf

The Casebook of Sherlock Holmes, by Arthur Conan-Doyle

Men Without Women, by Ernest Hemingway

Death Comes for the Archbishop, by Willa Cather

The Sherlock book is especially noteworthy, as it’s the last of the Sherlock collections to enter the public domain. Before, the Conan-Doyle of estate notoriously tried to keep suing movie adaptations of older Sherlock stories, using The Casebook of Sherlock Holmes as their legal bludgeon. Cory Doctorow has the story:

The estate's sleaziest trick is claiming that while many Sherlock Holmes stories were in the public domain, certain elements of Holmes's personality were developed in later stories that were still in copyright, and therefore any Sherlock story that contained those elements was a copyright violation. Infamously, the Doyle Estate went after the creators of the Enola Holmes series, claiming a copyright over Sherlock stories in which Holmes was "capable of friendship," "expressed emotion," or "respected women."

Thankfully, those lawsuits were thrown out. Next year, the public domain will be graced by a jolly little cartoon known as Steamboat Willie, starring a mouse named Mickey. That’ll be fun to watch.

Applied Xenolinguistics

There’s a new Avatar movie out! I really don’t give a shit, to be honest, but I did really enjoy this Atlantic article by Matteo Wong covering the invented language spoken by the movie’s blue aliens. Despite sounding like gibberish, it’s actually a fully-functioning language with thousands of words, a complete grammatical system, and variations of dialect and accent. Far, far more thought has been put into this fake language than James Cameron probably put into his English dialogue, if the trailers are anything to go by.

It turns out there’s a whole niche market for these fake languages. Wong:

Commissioning an entirely new language, which felt special for the first Avatar, is becoming a staple for immersive science-fiction and fantasy worlds. We’ve seen the invention of Dothraki and High Valyrian for HBO’s Game of Thrones, spoken and sign languages for the recent Dune remake, and bloodsucker-speak for Vampire Academy, to name only a handful. These languages are as functional as English, with internally consistent rules. In turn, neuroscientists have been able to harness them to better understand how the human brain processes constructed and natural languages, giving us new clues into what, exactly, constitutes a language to begin with.

The last part is especially cool: apparently all these fake languages are neurologically indistinguishable from natural languages. Your brain can’t tell the difference between Finnish and Klingon, and there’s something beautiful about that. The article is also a good recommendation for Arika Okrent’s In the Land of Invented Languages, which is great.

I, Chatbot

I’ve somehow gotten 1,000+ words into a literary news roundup in December without mentioning ChatGPT and LLMs until a few lines ago. I’m getting a little sick of reading about these, and I’ll bet you are, too. But here’s a good one.

Laura Preston spent nine months working as a “human fallback” for a real estate management company’s customer service chatbot. The setup is simple: whenever “Brenda” the helpful booking agent responds to a potential renter’s texts, the answer must be vetted by a human. There are dozens of these human fallbacks editing Brenda’s responses, most of them creative writing graduates, Ph.D students, and other members of the academic precariat for whom $25 an hour with zero benefits is a great deal. Their job is mostly to humanize “Brenda” while steering all conversations towards scheduling a property visit.

“I want a reservation,” wrote a prospect. “I’m currently on vacation. I’m Russian and I just got divorced with my American husband. He started seeing someone else and I want to move my things immediately when I am back.”

To this, Brenda wrote:

> We have 1BR starting at $1484. Do you want to come in for an appointment at 1 PM on Tuesday, Jun 11?

The timer began its countdown. I quickly amended the message.

> I’m sorry to hear that! Will you be able to visit the property ahead of your move? If not, I will check with our agents to see if they can accommodate video tours.

> We have 1BR and 2BR starting at $1484.

To be very clear, “Brenda” is supposed to be a real person. If you try to call the number it texts you from, a cheery voice of “Brenda” cycles through voicemail responses claiming that she’s so super busy being a superstar real-estate agent that she can’t possibly answer your question right now, but if you text her she’ll get back to you as soon as possible. The company line on this is strict:

Naturally some prospects grew suspicious. If a prospect asked if they were speaking to a bot, we were not allowed to say Yes. We were also forbidden to say I’m not a bot, because I’m not a bot is exactly what a bot would say. Instead, when someone questioned Brenda’s personhood, we were told to say I’m real!

Welcome to our new reality! It’s real! You can read the whole thing at N+1, or a condensed version at The Guardian. We’re only going to see more LLMs creep into our daily lives in the upcoming year, and I’m sure all of it will be great all of the time for everybody.

Happy New Year, and happy reading!

Man, what a fantastic Roman numeral. I’m going to miss it dearly.