The Log in Blog

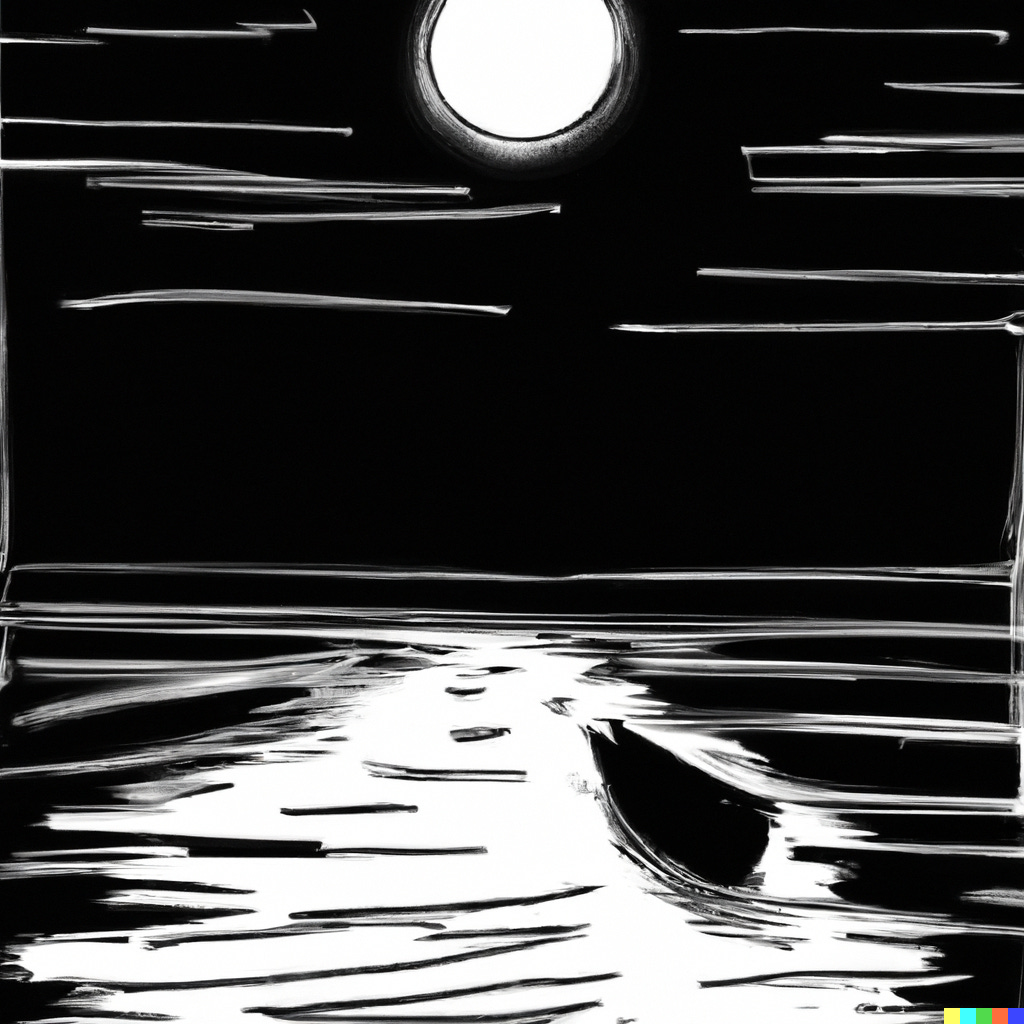

In the beginning, it was an actual log: a tree trunk, kept at the aft of the ship, light enough to float but heavy enough to stay where you threw it overboard. Seventeenth-century sailors would tie a rope around the ship's log, toss it, and sail on, letting the rope unspool. When the rope ran out, they reeled in the ship's log, reckoning the distance by the number of knots in the rope. The number of knots traveled was reported to the ship's navigator, who dutifully recorded the distance traveled. From this number, with a few swings of the sextant (for latitude), the navigator could reckon, with reasonable accuracy, where in God's great ocean the ship actually was. To help with future calculations, and to no doubt appease the insurance agents who underwrote the whole voyage, all of this was written down, along with a quick, diaristic report on the performance of the crew, the shifting weather, the passing of ships, and anything else the navigator or captain thought useful enough merit entry in the log-book.

Sailing metaphors have always had currency in English, and this particular is well documented. "Log-book" was used by sailors as early as the 1670s, shortened to "log" by 1842, and could stand for "any record of facts entered in order" by 1913. By the 1960s, you could log in to a computer.

It's hard to imagine a profession more distant from sailing than computer engineers. And yet, logs were popular with early computer designers, as their room-filling contraptions of punch cards and vaccuum tubes required extensive documentation shared among large groups in order to keep them functioning. The computers got smaller as their networks grew in the 1970s and 1980s, but the term stayed. By the mid-80s, there was enough going on in the world of USENET that a few enterprising users took to making digests of good discussions you might have missed, often with pithy commentary attached. Reel in the log from the web, and hear what's going on with USENET since you last checked.1

Then there was the World Wide Web. Almost as soon as the Web happened, there were countless online diaries, journals, and logs of every kind--that is, among the very narrow, nerdy slice of humanity that was using the internet in the early 1990s. As internet software improved, these personal sites were becoming more accessible and more hyperlinked. In 1997, Jorn Barger called these online writers "weblogs." Before long, they were just "blogs." By the turn of the millennium, Open Diary, LiveJournal, and Blogger.com were all open for business, offering webhosting for anybody who wanted to reel in their own log from the online sea.

The Blog is Dead, Long Live the Blog

You probably don't need me to tell you about the "Golden Age of Blogging" that followed. A thousand blogs bloomed, and the internet felt joyous and free and without sin. Like most Golden Ages, nobody knew that they were living in one, because it was full of as much sound and fury as any other time. There were endless arguments about the legitimacy of blogs and how--or whether--they fit into the landscape of journalism and literature at all. There were terrible blogs (Hipster Runoff), essential blogs (Bookslut), and plenty inbetween. As a young person who did much of his growing up on the internet at the time, it felt like an exciting, weird new time for writing. But the blogging boom turned out to be a bubble.

Social media swallowed up blogging entirely by around 2010. By 2014, it was dead. Whatever strange and revolutionary force blogging was, or might have been in the early aughts when citizen journalists and online magazines were emerging everywhere, most of that energy had been channeled by the turn of the decade into Silicon Valley's walled gardens. Worse, the whole web began its long cultural and economic pivot to video, which requires more time, talent, money, and attractiveness (let's not kid ourselves) than most writers have. And on top of all of that, the original generation of bloggers were no longer in their twenties. Blogging could work as a fun hobby, and maybe even a side-hustle, but it didn't build your 401(k).

OK, so blogs never died, but they definitely stopped mattering. Media startups like Huffington Post or Vox scooped up most of the big bloggers with a fanbase, while the energies of smalltime bloggers were absorbed by Twitter and Reddit. A few bloggers still exist, but the whole enterprise is so far out into the periphery of the culture in 2023 that continuing at blogging as a means of expression and communication, let alone career development or financial reward, reeks of lunatic obstinacy. The reasonable thing for me to do, if I wanted to get the world interested in weird bibliography, would be to talk about it while pursuing the latest TikTok challenge.

You Can Probably Guess Where This is Going

All of this is to say that I've been having trouble, lately, figuring out what to call what I'm doing here on Substack. Worse, I just came out of a dreadful January depression where even stringing a few words together felt impossible. And I love writing. But I was overthinking my work, second-guessing everything, mired in doubt. I had the yips. And this is supposed to be a fun lark to go alongside bigger projects.

It doesn't help that I'm on Substack, which is more of a platform than a genre. Plenty of people use it for actual newsletters, journalism, commentary, articles, research, investigations, and finely-wrought essays.

On the other hand, I like blog. Less formal than an article or essay, more wide-ranging than a report or a newsletter, very online but in a Web 1.0 kind of way with a reliance on old-fashioned words, pictures, and emails. And if the internet of 2023 is already deep into an extended sociocultural crackup, why not make like it’s 2003 and keep sending out email newsletters about philology and cybernetics? Why not retreat into the desert? Why not drift for a bit, then reel in the log? Why not blog?

It's free, it's weird, and it's hopelessly out of date. So I'm trying to reframe my work here as blogging. I drag in the log, count the knots, report the drift, and calculate where I’m at in the great world wide by consulting the wind and stars.

This doesn't mean I'm actually changing how I work or what I do. I still obsess over weird scripts, the history of writing, unusual books, and secondary orality. I'm just trying to find the right metaphor for what I already do, and to give myself permission to do what I do in my own weird way. (Robin Sloan also gave me permission last year; the act-like-it’s 2003 thing is his idea.) I don’t want to essay, to try, and grade myself afterwards for how effective my thesis statement is, and judge whether or not I have an effective conclusion. I do enough of that in my day job.

What I’d much rather do is take up my post at the appointed time, reel in the soggy log, count the knots, and see where I've been. I write up the results. My wife proofreads it. I add goofy illustrations. I post. It's therapeutic, it's free, and some people seem to like it. More people should do it. You could do it.

So if I'm spending a lot of time rechristening this enterprise as a blog here, it's only to give myself permission, in 2023, to be looser, rangier, and weirder in my amateur bibliophily—to explore, experiment, and iterate.

Coming into a new year, and coming out of a bad depression, this seems like the right time to rededicate and recommit. So let's try and use this creaky old form—the email newsletter, the long-form blog post—and see how far it takes us.

From the Archives

Goofing off with Haruki Murakami last week was fun, and a good example of what I’d like to do more of. Here’s another post that, although it took a bit of research, was a pure blast of joy to compose, and one of my favorite writings:

And that’s it for this week. Happy reading!