Hwaet We Want From Anglo-Saxon Translation

Should we translate Old English like a foreign language, or honor its weirdness?

Riddles in the Dark

Here's a riddle for you, #60 from the Exeter Book:

Ic wæs be sonde, sæwealle neah,

æt merefaroþe, minum gewunade

frumstaþole fæst...

Did you get it yet? No? Alright, here's a few more lines:

Fea ænig wæs

monna cynnes, þæt minne thær

on anæde eard beheolde...

It's obvious by now, right? Right?

Of course it's not. Our own modern English is so far from Anglo-Saxon speech that Old English is practically a foreign tongue, no more readable than Frisian or Icelandic. Looking at the riddle above, you might have caught a few basic cognates like wæs or beheolde, but if you can tell me the meaning of merefaroþe without a dictionary, then this essay is not for you.

The answer to that riddle, incidentally, is a "reed pen." Or, it probably is: the Exeter Book, which holds all the surviving riddles from the Anglo-Saxon period, provides no answers. Reeds, an anonymous Wikipedian points out, were not used for pens in early Medieval England. It's one of several Old English riddles that touches on books and scribing: answers to other riddles (spoiler warning for thousand-year poems) include bookworms, a pen and fingers, and a manuscript.

I read all of these riddles, in translation, in The Word Exchange: Anglo-Saxon Poems in Translations, edited by Greg Delanty and Michael Matto. The book is an anthology of every complete Anglo-Saxon poem except for Beowulf (which by itself is about one-tenth of all English poetry before the Norman Conquest). That means The Word Exchange is about as complete a collection of Old English poetry as any civilian could ever need, and if you read it cover to cover, like I did recently, then you've surveyed the whole territory. I enjoyed it, mostly. Like any anthology, some poems stood out more than others, and I was drawn to some subjects (exiled poets, lamenting wives, riddles about books) more than others (doctors' recipes, Bible stories, riddles about onions).

But what really stuck out to me in The Word Exchange was the translation: the editors brought in dozens of them, one for each poem, ranging from hardened Old English academics to practicing poets whose Anglo-Saxon ends at Hwaet! The editors' reasoning is sound: these poems span hundreds years and various styles, coming from many different authors (mostly anonymous) and dialects. The best way to capture this diversity is to bring in a cast of translators as broad as the poems themselves.

This also means that you get dozens of different philosophies of translation all in practice together, between the covers of the same book. Some translators stick closely to the classic Anglo-Saxon poetic mode: a four-beat line, with a strong caesura in the middle, heavily alliterated, loaded with kenning-compounds and sticking to Germanic words over French or Latin, as in David R. Slavitt's "Battle of Maldon": Forging them forward / shoreward, warward...

Others go for the sense of the thing in smooth, unruffled modern English, like Mark Halliday's nearly free-verse "Maxims": "To live well is to do what needs doing. If you have wise counsel, / speak it clearly; but when secrecy is wise, write silent words."

Helpfully, in addition to an introduction that lays out the many problems of trying to translate Old English into modern English, The Word Exchange also includes an appendix full of short essays by the translators, explaining some of their choices and ideas. What stuck out, again and again in these sections, was a sense by everybody, even the free-verse modernizers, that there is a specific way most Anglo-Saxon poetry is supposed to sound: a gravelly, grave, incanting voice over a crackling fire on the misty moor at midnight, telling stories of warrior-poets who leave their mead-halls to ride the sea-roads to a foreign fastness for sword-sport with their foes. The editors call this ur-scop "Anonywulf." We might also call him Generic Anglo-Saxon Poem Guy. Like all literary influences, Anonywulf could be embraced or rejected, but he can't be ignored.

Much of that has to do with Anglo-Saxon's connection to English. When you're translating a Chinese poem, everybody understands that you're going to have to make extreme compromises in sound, pattern, and shape to make all those hanzi fit in English. The languages are wildly different. But Anglo-Saxon is English; shouldn't it be possible to recreate something of the original in our own modern dialect? Isn’t there something we can keep from the ancestral tongue? Is it truer to turn Beowulf into a slang-talking rudeboy, or is it caving in to intellectual cowards who can’t be bothered to learn a simple þ and show the simplest bit of interest in the deep roots of their language? In this way, Anonywulf calls to translators from across the centuries.

But the weird thing is, even though Anglo-Saxon poetry is a thousand years old, the voice of Anonywulf has only been with us for about a century.

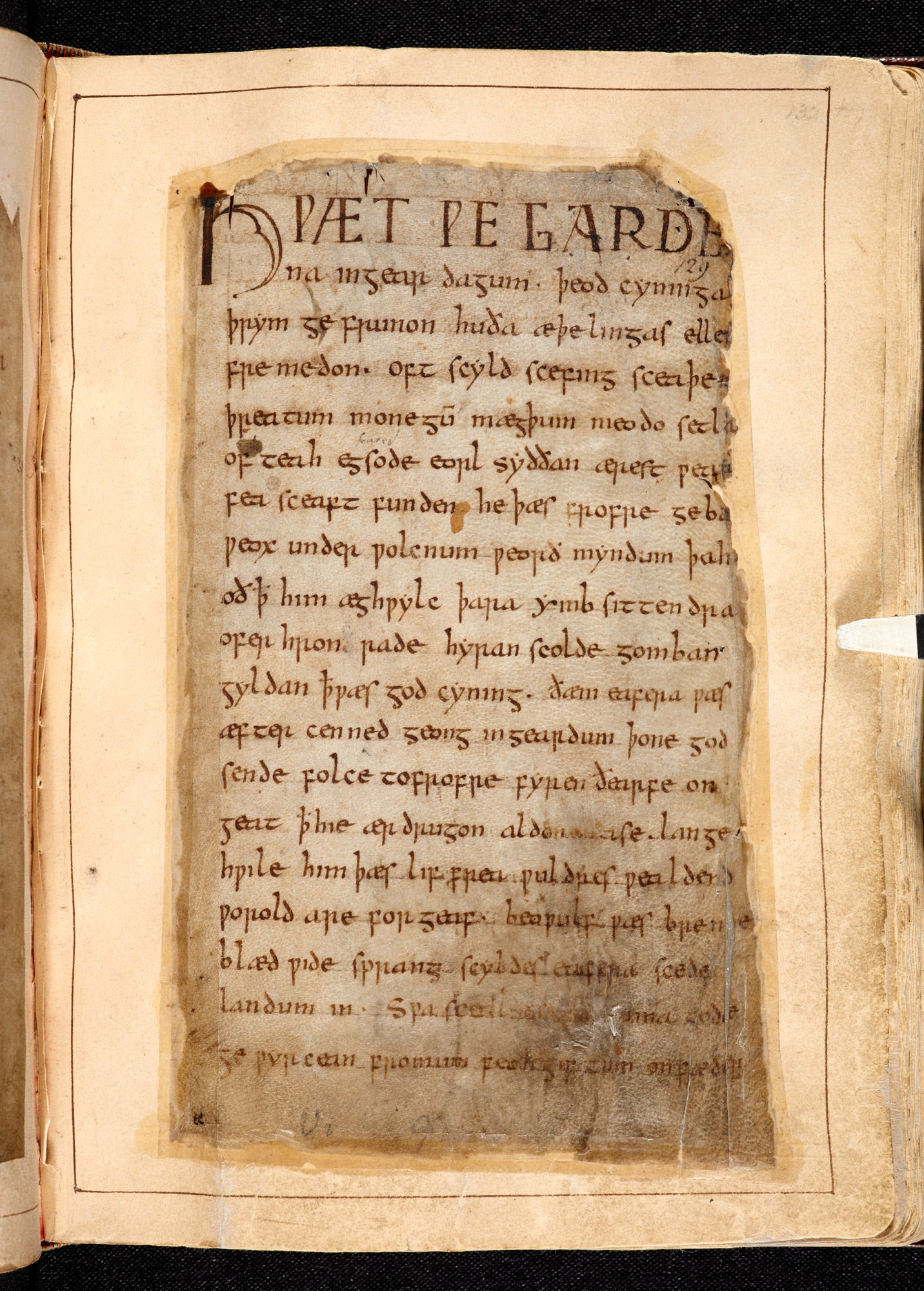

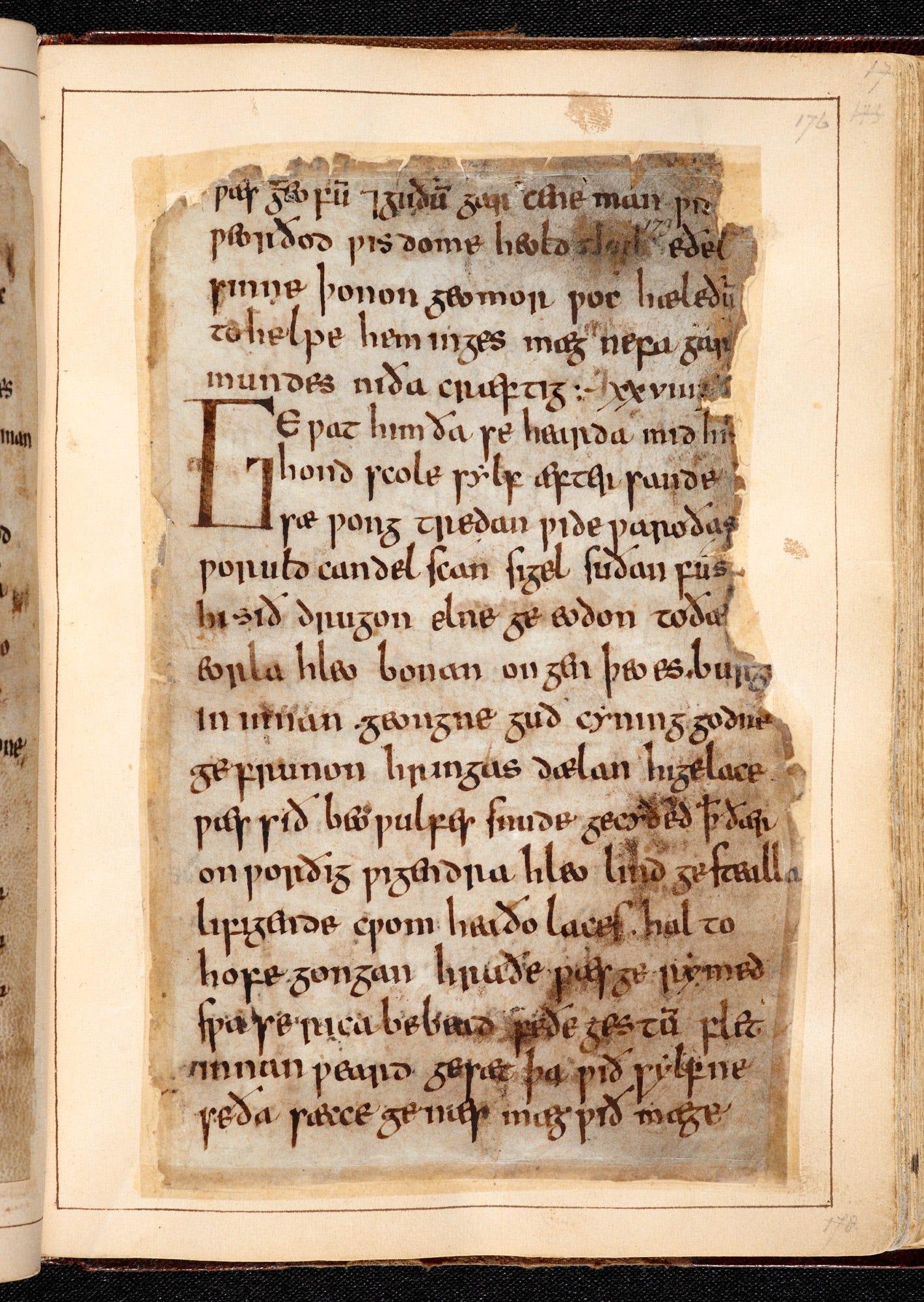

After the Norman Conquest made French the dominant language of England's elites, Anglo-Saxon speech and culture were seen as backwards, primitive, and beneath attention for most educated Englishmen. Half a millennium later, in the Elizabethan era, as gentleman-scholars took up antiquarianism as a hobby, you start to see a few oddballs study Old English, like Laurence Nowell, but the subject remained a minor curiosity: unlike Latin and French, you didn't need it for professional advancement; unlike German or Italian, you couldn't use it to visit distant lands; and unlike Greek or Hebrew, it couldn't help you read the Bible, Homer, or other ancient classics. Nobody even knew how much Anglo-Saxon poetry was around, or what kind it was. It was only in the 18th century, with nationalism's rise, that British scholars began to take a scientific interest in their deep past and catalogue the collections moldering away in libraries across the island. An 11th century manuscript that had been catalogued sometime in the mid-1700s as a history of Denmark's heathen kings turned out to be Beowulf.

By 1800, there was a healthy interest in Old English literature, with translations of the prose and poetry regularly going to press. Most of them, though, like Sharon Tate's 1805 translation of Beowulf (the first in modern English), were academic, not artistic. Tate's Beowulf translations were meant as exercises for illustrating his ideas on the philology of Old English. The next Englishing of Beowulf was even more donnish: J.J. Conybeare's English prose version was actually a gloss on his Latin translation from the Old English, which is just the biggest Oxford-boffin thing that's ever happened. Over the next decades, matters hardly improved. "The interest in Old English in the nineteenth century," Chris Jones writes, "is philological rather than acoustic."

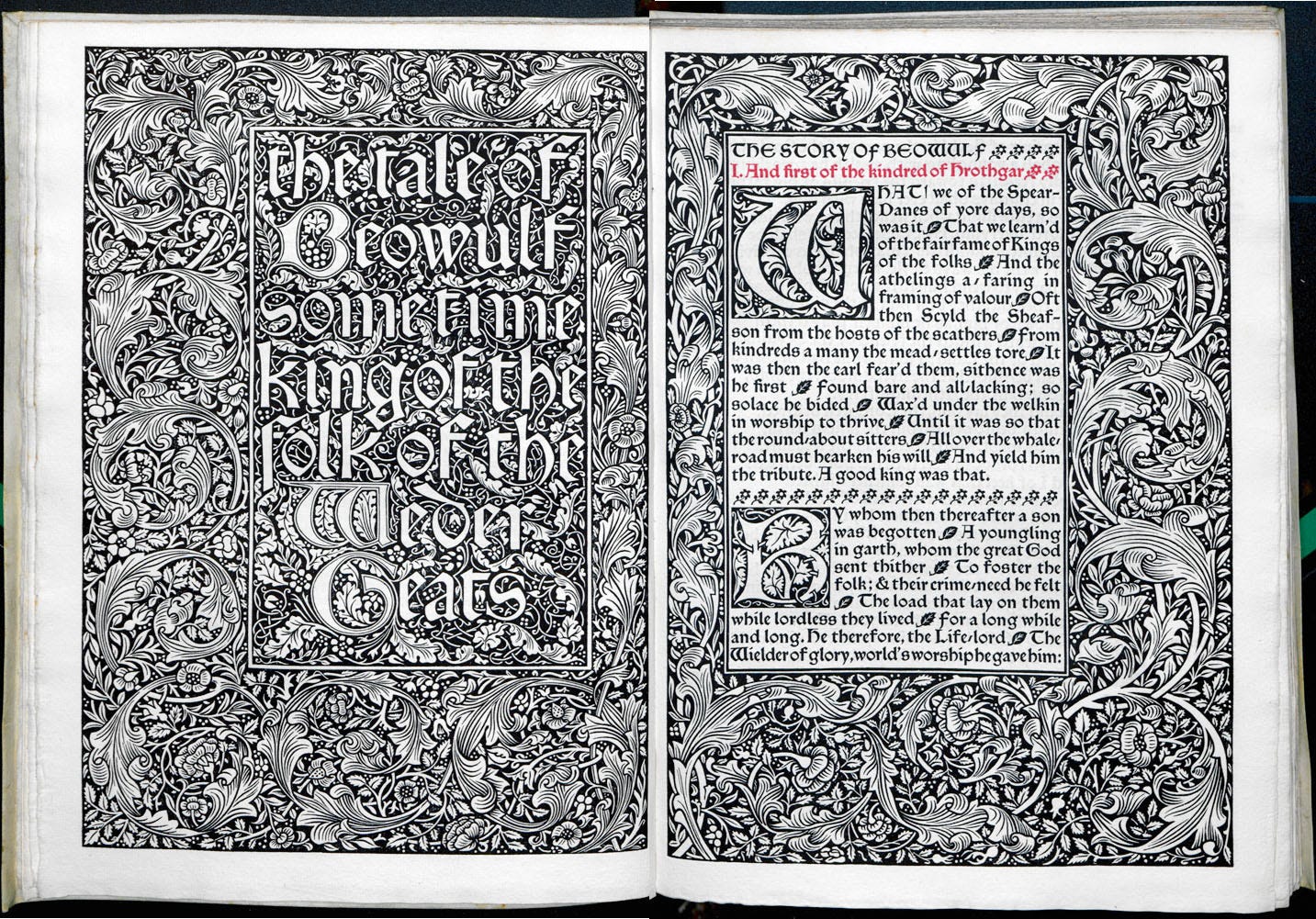

In a century of fervent English nationalism, it's striking that only two major poets expressed any interest in the oldest poetry in the language: Tennyson, who made an attempt at "The Battle of Brunanburh" , and William Morris, who translated Beowulf in partnership with A.J. Wyatt for his Kelmscott Press. Here, for the first time, Anonywulf rears his helmeted head: both poets keep closely to the Anglo-Saxon poetic style of tub-thumping, Germanic alliteration, leaning hard into the alien tones of the language. But both translations were failures: Tennyson's "Brunanburh" is one of his lesser-known works and he never tried that style again; and the Kelmscott Beowulf was printed in a limited, expensive run of only 300 copies.

But even if Tennyson and Morris didn't catch the attention of the British public with their Anglo-Saxon, there was one poet who caught what they were doing and ran with it. In 1911, Ezra Pound was an American expat in London who had left his country a few years earlier with the modest goal of revolutionizing poetry forever. Most people today agree that Ezra Pound succeeded in that goal, though usually for his later achievements, like editing Eliot's The Waste Land, publishing the earliest translations of classical Chinese poetry that weren't garbage, writing the postmodern epic Cantos, or establishing a legal precedent for poetic insanity as a protection against treason charges. But for all his globe-trotting omnivorousness, one of Pound's most lasting achievements as a poet and translator was a quirky experiment in translating his own language.

In 1911, Pound set himself the task of translating the Anglo-Saxon "Seafarer" in the way that he thought all poetry should be translated: with careful attention to replicating not only its meaning and resonance, but its vocabulary and sound-patterns, too. Probably he took a look at a recent translation, like Albert S Cook's from a few years earlier:

I can sing of myself a true song, of my voyages telling,

How oft through laborious days, through the wearisome hours

I have suffered; have born tribulations; explored in my ship,

Mid the terrible rolling of waves, habitations of sorrow.

Fine enough as a bit of modern English verse, but Pound wanted something like the real thing. Here's his take on the same opening lines:

May I for my own self song's truth reckon,

Journey's jargon, how I in harsh days

Hardship endured oft.

Bitter breast-cares have I abided,

Known on my keel many a care's hold,

and dire sea-surge, an there I oft spent

Narrow nightwatch nigh the ship's head

While she tossed close to cliffs.

Strictly speaking, Ezra Pound's translation is bad. It's full of all kinds of misreadings and mistakes, with weird added details not present in the original and words that look like modern English, but have a very different meaning in Old English. Pound calques Breostceare straight into "breast-care" to keep the sound of the original, even though the word was standard Anglo-Saxon for "anxiety". He extends, compresses, and inverts much of the detail and story in the text, in order to keep the dense webs of alliteration intact.

Most rebelliously, Pound drops the final stanzas of the poem, which describe the glory of God and the importance of Christian salvation, because Pound believed that Christian scribes full of bitter breast-cares about this pagan song tacked them on at the end, to avert the gloomy ending with its burial, dirt, and death.You can get a very full account of the "mistakes" here. Pound's Old English is very often wrong, in the academic sense, but sonically, it's about the closest any serious artist has ever gotten to expressing the feeling of Old English until maybe Paul Kingsnorth's pseudo-OE that he used in his novel The Wake.1

And the sound of "The Seafarer" is marvelous. Chris Jones identifies five tricks Pound uses to Saxonize his English:

He lets syllables with primary and secondary stress fall proximately, often putting long stresses right next to each other in ways that are rare in modern English. Many poets, and many more editors, would shy away from a cluster of long syllables like "self song's truth," but Pound lets it rip on the first line.

Pound uses falling rhythmic patterns more often where the long syllable is upfront (i.e., trochees and dactyls), which is more common in Anglo-Saxon and its Germanic cousins, but rarer in iambic-heavy modern English.

Clashing opposites in sound, especially on either side of the caesura in the middle of each line. Say a line like "While she tossed close to cliffs" and you'll feel the workout in your jaw.

Avoiding articles and short prepositions when possible, which were less common in Old English.

Frequent use of compounds, some calqued directly, and others yoked together from spare parts lying around in the original when it's easier, as discussed above.

Put all of that together, and you've got the voice of Anonywulf, the melancholy Anglo-Saxon warrior prince, sitting by the fire, chanting about exile and war in stately, blunt English. Auden used it, and so did Edwin Morgan and Richard Wilbur and W.S. Merwin and W.S. Graham, and Seamus Heaney in his Beowulf. The poet Thom Gunn praised Pound's "loosening" of Old English as "one of the most useful and flexible technical innovations of the century." It was certainly one of the most influential. This is not to say that any of these poets ripped off Pound; rather, they all labored under the breostcare of its influence.

Pound's invention could be rejected or adapted, but it could not be ignored. It's always dangerous, when speaking of literary changes, to give credit to one man, much less to one poem, but if any poet is responsible for helping Beowulf speak less like a Victorian gentleman, it's Ezra Pound.

Here he is reading it, in the rolling, carnival-barker style that he favored for his public readings. He even brought his own drum, apparently.

You can dislike this stuffy, artificial approach to Old English—many do, including many of the translators in The Word Exchange. But for all its corniness, I love the sound of Anonywulf, and I think he’ll be with us for a while yet.

From the Archives

If you liked reading about translating one ancient epic, why not read my words about the ancient-est, epic-est of all epics?

The Epic of . . . Bilgamesh?

[Note: this post has been revised from its original version published in April of 2022.] The Epic of Gilgamesh is very old. Even the standard version compiled three thousand years ago was based on poems that were another thousand years old, as far away from the editors as

Links!

Authors call on the FTC to investigate Amazon as a monopoly in the bookselling industry.

Why Read John Milton? Because Ed Simon is writing about him, and when Ed Simon writes, I read.

The Ornamental Hermit Craze of 18th Century England. Having just finished Tom Stoppard’s Arcadia (as good as they say it is, highly recommended), I was unusually ready to read about this very niche thing.

Gary Saul Morson wrote a book on “The Russian Classics, and Why They Matter.” I will be reading it ASAP and probably covering it here.

Bonus Track

Look, I also didn’t start this newsletter knowing that after a few years, I’d get bitten by a horrible, incessant urge to start making ambient music with synthesizers. I am as baffled as anybody else by this recent turn in my life. And I will keep blogging about books, rest assured. But man, people are on YouTube. I have more views after three months of posting music there than I have in all my years of blogging. So here’s my latest one.

And that’s all for this installment. Happy reading!

Scucca ingengas! Thu must rede The Wake, or Wodn taek yer oxgangs!