So You Want to Invent a Writing System

Of Orcs and Orthography

Preamble

Summer is here, and my classroom is closed for the next eight weeks. Most teachers use their breaks for beach trips, renovation projects, volunteer work, job training, sleeping in, and other kinds of useful, restorative things. I just use the extra time to read until my eyes desiccate. This is an especially good season for big, ambitious reading projects: one of mine will be revisiting The Lord of the Rings for the first time in nearly two decades, reading in and around Tolkien’s epic in my own bibliomanic ways. As such, expect a lot more elves and orcs in this blog over the next month or two.

One thing I’ll be looking at closely are the languages and scripts of Tolkien’s extended universe. If you’re the kind of person who reads literary blogs, you probably don’t need me to tell you about Tolkien’s invented scripts. Originally, all that business with orcs and elves and ringwraiths began as exercises for what he called his “secret vice” of language-making.

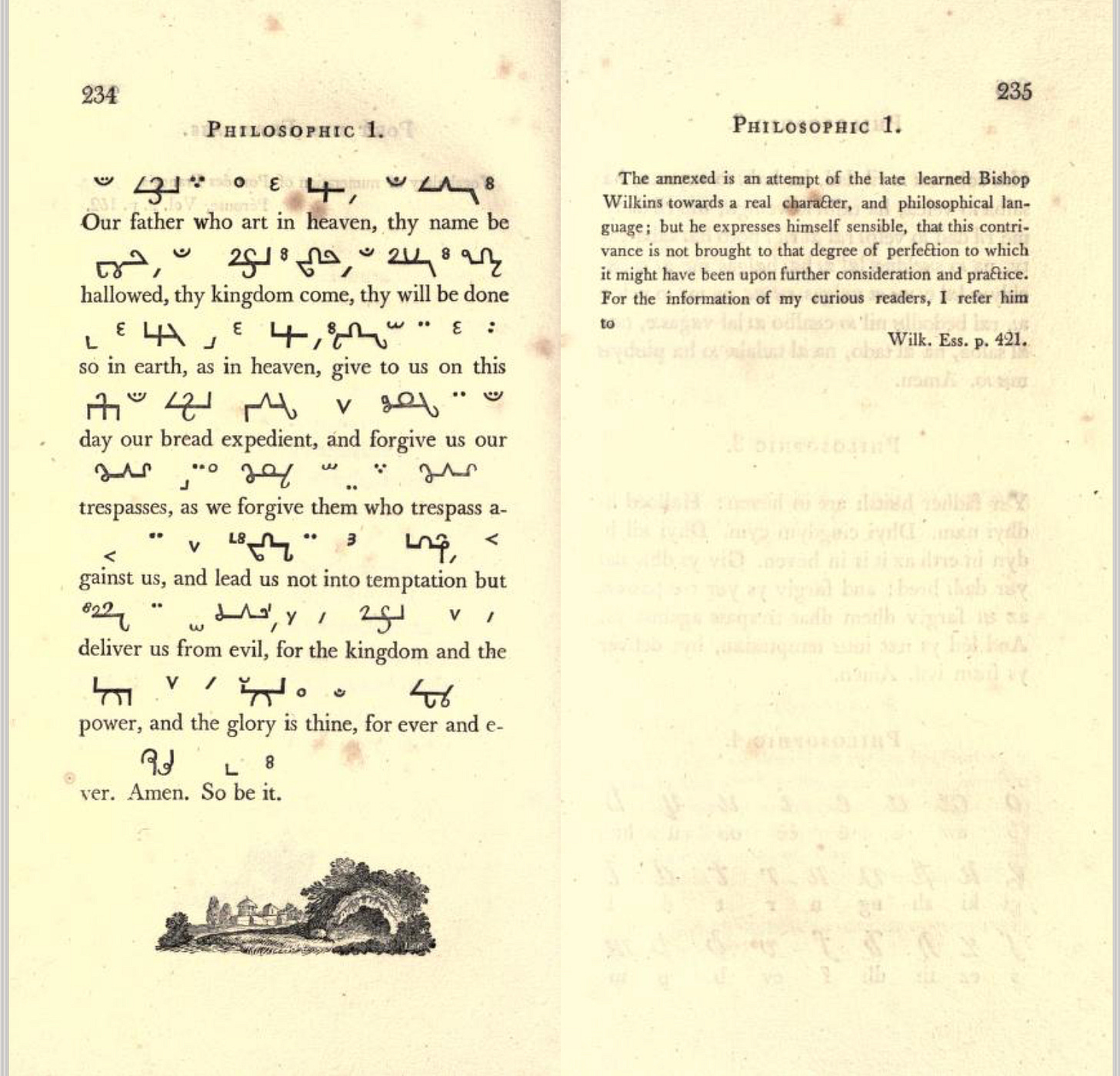

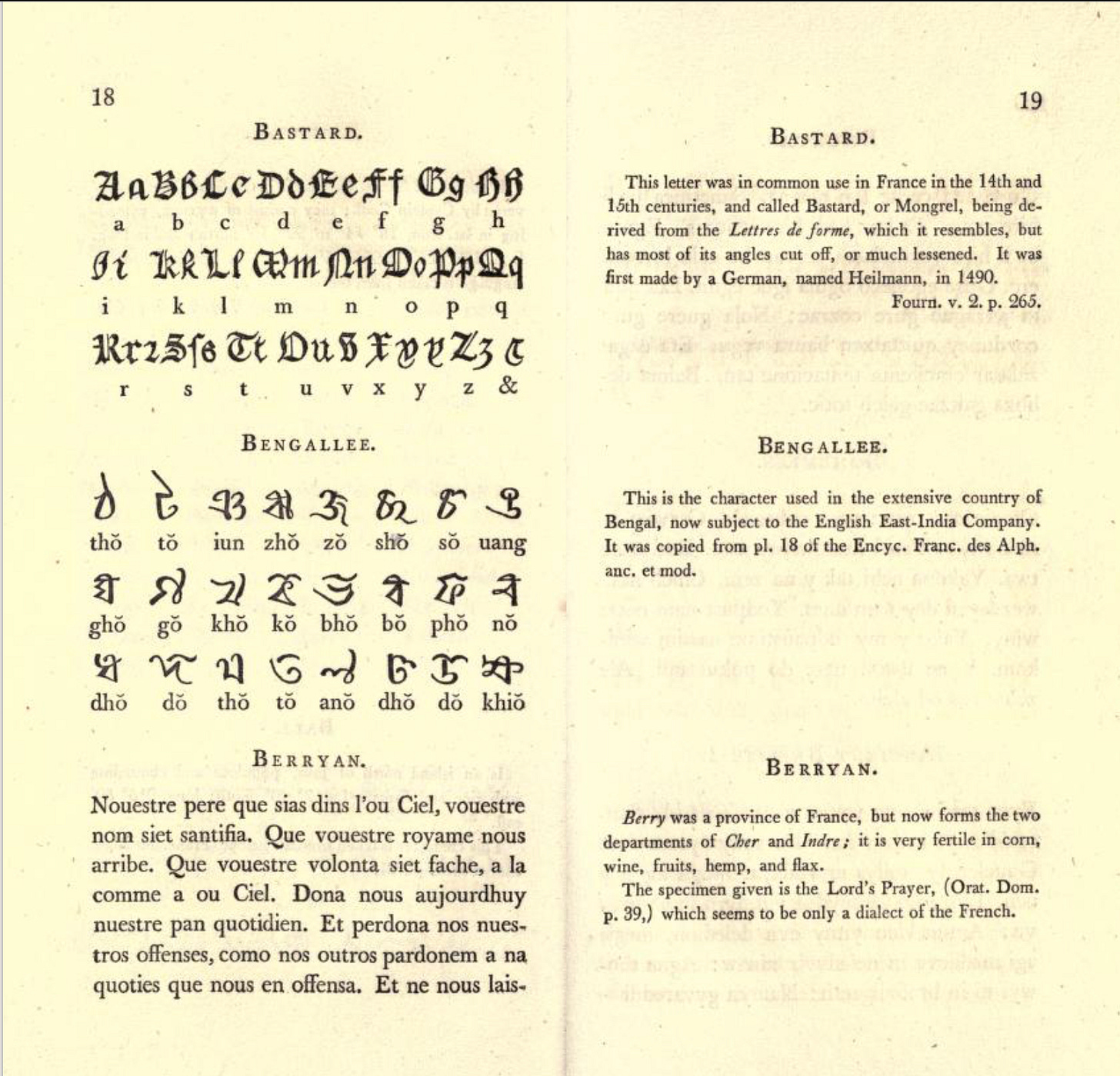

But before we look too much at Tolkien’s accomplishments, it’s useful to stop and ask: how do you make up a writing system, anyway? Making a constructed language, or conlang, is harder than it looks. Most of them, from Thomas More’s Utopian Alphabet to the glyphs in the background of the Star Wars movies, are basically a glorified cypher of the Roman alphabet. This might work for set-dressing on a TV show, but if you’re trying to base an epic around your fake languages, like Tolkien was, you need to do better than a cypher.

So let’s think our way through making a realistic, usable script. We’ll look at a few fundamentals, much of it probably half-remembered from reading David Peterson’s The Art of Inventing Languages and Arika Orent’s In the Land of Invented Languages ago. You should definitely consult those for longer, more professional considerations of conlangs. But if you just need a crash course on making a writing system, this essay is for you.

Materials & Methods

Let’s assume you’ve already have a spoken language ready to go. This could be a real language, but for this guide we’ll assume it’s fictional. (Although there are plenty of fascinating alternative scripts invented for English.)

Before you scratch out a single glyph of writing, it’s important to understand the material and cultural conditions of the script’s users. You have to know what kind of people (or aliens, orcs, etc.) use this writing, what they write with, and why they write.

Start with who reads and writes. Universal literacy is a given in any modern, developed country because nation-state politics and global capitalism work a lot more smoothly when everybody can read and write. We use our scripts for everything: business, government, education, reporting, entertainment, religion.

But our modern, text-saturated environment is only one kind of textual culture, and a relatively recent one in the 5,000-year history of writing. Of course, for almost all of that time—until the last century—it was a given that most of the world’s adult population didn’t have elementary reading or writing skills. That doesn’t mean, though, that a minority was completely literate while everybody else was digging ditches. In a few societies, like the ancient Fertile Crescent and pre-Columbian Mexico, the evidence does point to a monopoly on writing by tiny castes of priest-scribes, who used their skills for religious ceremonies and administrative tasks. But in many cities, from 4th-century BC Athens to 1st-century Rome to 8th-century Changan to 17th-century Edo, there’s evidence of widespread literacy among middle-class professionals who could read and write for business reasons.

Many cultures even had multiple scripts, used by different groups for different purposes. Priestly writing systems, like Egyptian hieroglyphs, were complex and required long years of elite education to master. But within a few centuries of its invention, there was already a simplified Hieratic script used for administration. In medieval Japan, where Chinese kanji were the script of elite men, the simpler hiragana script became known as women’s writing because it was so easy, even uneducated women could use it. (Those frivolous entertainments that the ladies wrote went on to become the foundation of Japanese literature.)

Of course, fictional scripts used by fictional cultures don’t have to correspond to real history. All this is only to say that before you go about making a script, you should think carefully about how and why this script exists, and what people use it for.

Consider how Tolkien’s characters used his scripts. All elves seem to be literate, often in multiple languages, because they can live forever and one has to pass the time somehow; but being a flamboyant, stagey culture, many seem to prefer memorization and recitation instead of writing. Dwarves, being practical urban craftsmen who need to carefully manage their limited resources, seem to have high rates of literacy in their script, written in straight lines that are easy to carve in stone. Hobbits seem have to the literary habits of their rural English models: gentleman-farmers like Bilbo and Frodo are literate, with Bilbo even writing a book of his travels for the sheer pleasure of sharing it, but for a lower-class hobbit like Samwise to read is unusual enough to be remarked on by others. Gandalf, of course, can read everything—even ancient texts moldering away in Minas Tirith that no living humans can understand.

All this is to say that Tolkien clearly put a lot of thought into which of his characters could read, and why they would—or would not—need literacy to live their lives. He developed a number of scripts, and even variants, to reflect the varied history and use-cases for different types of writing by different people for different reasons.

Writing Systems

With that out of the way, we can get into the nuts and bolts of writing. But before you start scratching out yet another Roman alphabet cipher, it’s important to ask if you even need an alphabet. Let’s look at our options, based on historical precedent.

1. Alphabet

Alphabets are so overwhelmingly dominant in European languages that most of us tend to think that alphabets just are writing. In everyday English speech, you might hear somebody talk about the Arabic or Korean alphabet, even though they aren’t alphabets at all.

To be clear, an alphabet is a writing system that uses individual letters to represent consonants and vowels. That doesn’t mean you need to have an exact 1-1 ratio of letters to sounds—most languages, like English, have more phonemes to pronounce than graphemes to write with—but an alphabet should be able to represent any individual part of a word in a regular, reliable way. Most invented scripts, like Tolkien’s, are alphabets for the simple reason that modern fantasy and sci-fi are the products of Western, alphabetical cultures who think of writing in alphabetical ways.

2. Abjad

The alphabet’s closest relative is the abjad, mainly used today in Arabic and Hebrew. Like alphabets, abjads are made up of individual letters that stand for individual sounds, except that they only represent consonants, not vowels. It’s possible to write English as an abjad (lk ths, fr xmpl), but you run into difficulties pretty quickly (consider Hamlet’s monologue: t b r n t b—tht s th qstn). But for consonant-heavy Semitic languages, abjads seem to work just fine.

3. Abugidas and Syllabaries

These two are usually classed differently, but functionally they’re similar. Abugidas are common in South Asian writing and the Ethiopian Ge’ez script. Unlike alphabets and abjads, which work at the level of individual sounds, each letter of an abugida represents a consonant and a vowel together. For most, a consonant is written as a base, then receives an extra mark on or next to it to indicate the paired vowel sound. You can see it clearly in this Wikipedia table for Devanagari, used for Hindi and other South Asian languages:

The root क always makes a k sound, while the extra bit written on the side, top, or bottom changes its vowel.

The Japanese kana syllabaries also work this way, except each symbol is arbitrary: the symbols for ka, ki, ku, and ko all look completely different, and just have to be memorized.

4. Logographs

And then there are logographs. I’ve written about the joys and frustrations of logographs in other posts, but here’s the simple version: unlike alphabets and abjads and abugidas, where graphemes only represent sound, each unit of logographic writing can represent both sounds and meaning. In a logographic system like Chinese hanzi or Egyptian hieroglyphs, you might have two or three or twelve different symbols that can all make the same sounds, but are visually distinct. This means that logographs have remarkably little homography—words that are spelled identically but have completely different meanings, like the English tear (as in crying) and tear (as in rip apart).

Logographic systems are fascinating, but they’re also hard to understand if you aren’t used to them. More importantly for language inventing, this introduces all kinds of headaches with spelling, as you’ll have to specify the logograms used for every word. They also multiply the amount of distinct graphemes you have to make—Chinese, after all, has tens of thousands of hanzi, and even elementary texts use hundreds.

5. Others

Just about every major writing system comes from one of the categories above, but one of the fun things about conlangs is that we don’t have to restrict ourselves to following existing models. We can also learn from the oddballs, freaks, and outcasts of writing.

The specter of pictographic writing—picture-words—lingered under European descriptions of Asian and American indigenous writing for centuries, though what looked like picture-writing to colonizers has always turned out to be a more mundane, logographic writing system. But some artists have tried writing with pictograms, like Xu Bing’s Book from the Ground, a novel told in entirely in icons and emojis.

There are also quipu, the famous knot-writing system of the Incas. Pretty much every single claim about quipu is contested, and nobody knows exactly what they really are or how they were really used, but they were almost certainly used for communication of some kind. Quipu also raise the possibility of other physical, three-dimensional writing systems, though you’ll have to think carefully about how sculpted letters would be created, displayed, read, and preserved (if at all).

Once you’ve picked a system (or invented one), you can finally move on to actually making your graphemes, whether they’re alphabetical letters, syllabic glyphs, logograms, tangles of knots, swatches of color, geometric shapes, ink blots…

Orthography

Orthography is just the fancy Greek term for “correct writing,” covering all the rules and conventions that govern a writing system. Orthography doesn’t have to be a single, fixed thing: the very concept of it is bound up in the invention of printing and the development of nationalism, both of which encouraged making writing more standardized and reproducible. The very idea is prescriptive, rather than descriptive: enforcing what writing should be, rather than how it might actually be used.

For lots of very good reasons, modern English speakers are wary of orthography, and the ways it’s often used to elevate the speech and writing of some groups over others. At the same time, orthography is a useful brake on linguistic evolution, keeping the reading and writing of places that are distant geographically or chronologically. Orthography is the reason why Shakespeare, writing after the print revolution, is far more readable today than Chaucer, who died before it.

This can be part of your conlang’s context: Tolkien modeled his scripts on the low-orthography context of medieval European scribal traditions, with styles and fonts changing from era to era. This gets you scenes like Gandalf’s trip to the Minas Tirith archives, full of books which Denethor admits are pretty much illegible due to the changes in style and language.

With all that said, here are a few considerations for orthography, whether you have a lot or a little:

Fonts, hands, scripts, and cases: are there different writing styles and formats for your graphemes? Are they distinguished by social class or purpose, or just a matter of preference, as in arguments over Times New Roman versus Helvetica? Is there a joined version of the script, like cursive? Or, if the letters are already joined, is there an unjoined form? Is there an upper-case and lower-case, as in European languages, or is the writing in a single case, as in Georgian or Ge’ez?

Directionality: what is the basic orientation of your script? European languages are read from left to right, while Arabic and Hebrew are read from right to left. Both are written in rows moving from top to bottom. Traditional Chinese and Japanese writing flows in vertical rows, read from right to left. Some Greek and Etruscan scribes used boustrophedon, where the direction of the words would turn around at the end of the line, going form left to right, then right to left, then back towards left to right. Or your conlang could move, like the Lilliputians, who write “aslant,” Swift writes, “from one corner of the paper to the other, like ladies in England.”

Spacing: we tend to think of spacing as essential in writing, but putting spaces between words is relatively recent, only starting around a thousand years ago in Carolingian France. Spaces between words would have been an extravagant luxury to most writers in most times, when writing materials were costly, but with the low cost of modern printing, just about every contemporary written language has made the jump to spacing.

Punctuation: once again, punctuation feels important for language, but most of them are a medieval European contrivance. Most writing systems never used punctuation marks until they were introduced by Europeans. They usually indicate the rhythm (like a comma versus a period) or tone (question mark or exclamation point) of writing, but it isn’t hard to imagine alternative non-phonetic symbols you could introduce to perform different functions in writing. But like spaces, they’re less necessary than you think.1

Correspondence: how closely do the graphemes and phonemes of your conlang match each other? No living phonetic system has a 100% match between the way something is written and the way it is pronounced, though some come closer than others. English, of course, is an orthographic nightmare, one of the few written languages in the world where people compete to spell obscure words. If your conlang is supposed to sound authentic, a 1-1 correspondence is suspicious; on the other hand, inventing an English-style orthographic jumble might be adding unnecessary complexity.

Conclusions

This idea of balancing between overly-perfect and needlessly complex correspondence seems like a good place to wrap this up, and a useful goal for the whole project of an invented writing system. Every human writing system has its quirks, complications, snags, and exceptions. There is some part of every system that is also elegant, inspiring, and useful. The trick, in a good conlang, if you want it to look authentic, is to come up with something that neatly navigates between the two poles.

Again, this only a very cursory glance at a big, complicated topic. You can read more about them here and here, or check out those books mentioned above. My goal here is only to provide a basic framework so that, should you want to start making a language, you would know where to start and what to do.

Not that I’m going to try my hand at this anytime soon. Making up a language is a lot of work, and I’ll be looking more at how Tolkien did it in this space in the next few weeks.

Bonus Track

My other big project for this summer is to make more music with my synthesizers. I’ve started recording and uploading them for fun. These bonus tracks will occasionally appear in future posts. As with Musement, they’re meant to be free, fun, irregular exercises for you to ignore or enjoy as you please. Happy reading!

Don’t tell my students that.