The Goodreads Scam

What recent extortion schemes tell us about the Internet's favorite book site

Extortion is having quite a year. Computer manufacturers, chemical companies, video game developers, the National Basketball Association, insurance companies, Kia Motors—all have been victims of high-profile data extortion schemes, their trade secrets stolen and held up for huge amounts of Bitcoin (crypto money being the preferred currency of hacker gangs, sex traffickers, and libertarians). Ransomware attacks even made national headlines when JBS Foods and Colonial Pipeline were paralyzed by extortion schemes. The cost of beef and gas soared for a few days. Americans panicked. The gangsters got paid.

The extortionists have now turned to the most lucrative field of all: literature. Authors are receiving anonymous emails filled with warnings like “EITHER YOU TAKE CARE OF OUR NEEDS AND REQUIREMENTS WITH YOUR WALLET OR WE’LL RUIN YOUR AUTHOR CAREER.” They follow all the rules of the ransom note genre, reminding the authors that they are being watched closely, that the deal is off if they alert the authorities, and that their chance of a positive outcome is getting slimmer by the minute.

But what, exactly, could they be extorting poets and romance novelists with?Have they obtained their crummy, embarrassing first drafts? Scolding notes from a sensitivity reader? The true identity behind their pen name? Not quite. “PAY US,” they write, “OR DISAPPEAR FROM GOODREADS FOR YOUR OWN GOOD.”

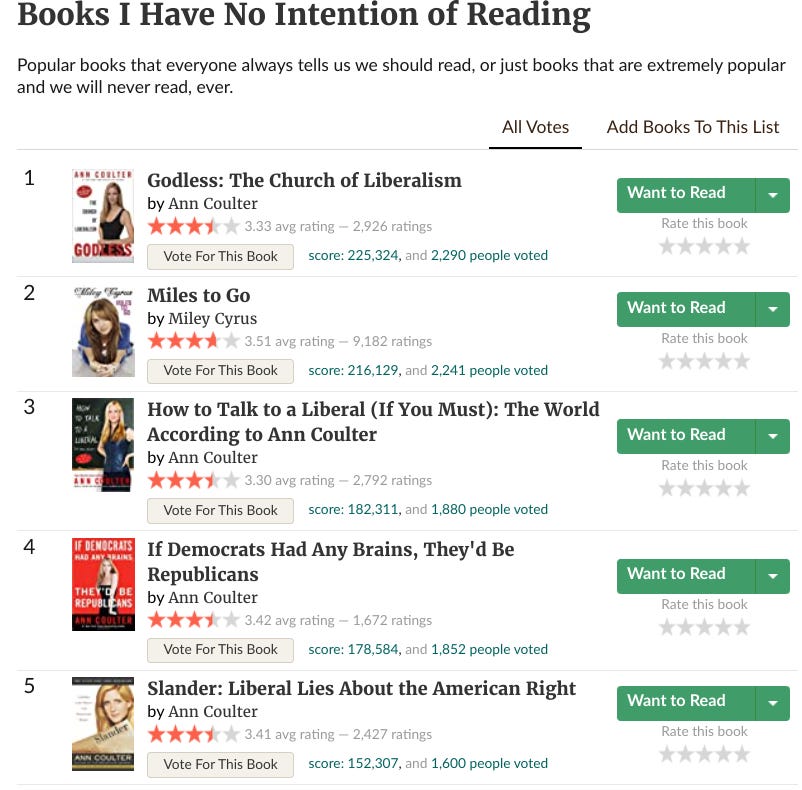

Yes, the scammers are targeting authors on Goodreads, the social media site for books. If the author doesn’t pay--two hundred dollars seems to be the usual rate--their books are overwhelmed with fake accounts dropping negative, one-star reviews. The more sophisticated ones leave little, pre-written comments like “Crappy book,” “Just a pathetic book. DNF” and “Full of bitterness and religious bigotry. Avoid.”

And that’s pretty much it. Nobody gets physically hurt, no industry is shut down, no secret data is leaked. A book just gets a low average rating on Goodreads. OUR SERVICES ARE QUITE CHEAP AND YOU CAN EASILY AFFORD IT,” ransom note says.

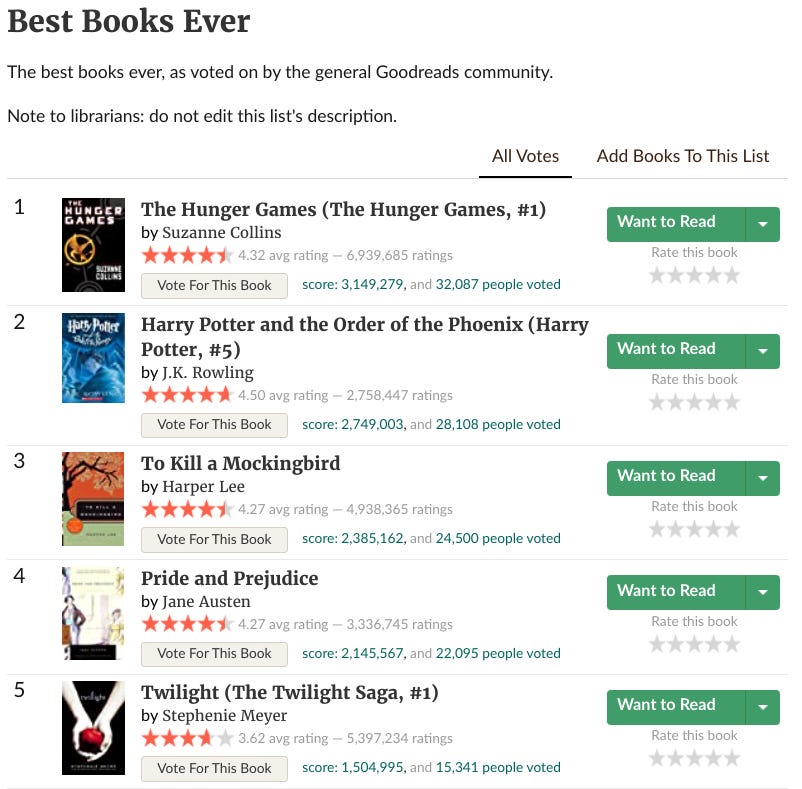

Although their grasp of English isn’t phenomenal, these scammers aren’t stupid. They’re trying to hit authors where it hurts—where they have the most leverage. And Goodreads, unfortunately, is a big deal for authors. With something like 120 million users (with the caveat that the Internet is mostly bots now) Goodreads is the largest book-based social site by far. Authors and publishers find their audiences there. Amateur book reviewers have launched careers on the strength of their Goodreads fame. Some two billion books have Goodreads pages with reviews, content tags, related books, and publisher data. After Amazon, Goodreads is where most people go to find a book or author online—which is why Amazon bought Goodreads in 2013. Goodreads matters.

But does a book’s average rating on Goodreads really matter for its success? Does an avalanche of fake reviews really have financial or critical consequences for authors?The honest answer is: we just don’t know. Goodreads doesn’t share most of its data or the algorithms that sort its lists, recommendations, and search results. They don’t share those things because they’re too valuable: Data is their real product.

Goodreads probably knows quite well how much a star rating affects a book’s success. They know how ratings and reviews influence its placement in recommendation lists and search results. They know how well a given book, author, or review travels, showing up in other pages, recommendations, feeds, lists, and shelves. They definitely know how users tag their books.

These tags are probably crucial to Goodreads’s success. Users make these tags themselves, sorting by whatever they want: Mystery, Books by Women, Uruguayan Books, Erotic Books, Mermaid Books, Erotic Mermaid Mysteries by Uruguayan Women. In this way, users show Goodreads how they organize their books: what matters to them, what they like, how they think about different kinds of books. Discussing the possible value of these tags and other data, a team of media researchers at Post45 compare Goodreads to a company whose business model we know much more about:

Like Goodreads, Netflix has a massive microgenre system for its video content, featuring hyper-specific genres like "Deep Sea Horror Movies" and "Romantic Dramas Based on Classic Literature." To assemble these 70,000+ "altgenres," Netflix "paid people to watch films and tag them with all kinds of metadata," as Alexis Madrigal reported in 2014. "When these tags are combined with millions of users' viewing habits, they become Netflix's competitive advantage," Madrigal argues. "The data can't tell them how to make a TV show, but it can tell them what they should be making." By tagging books with their own extremely detailed metadata, Goodreads' 120 million users perform a similar service for Goodreads and Amazon, but they do it for free.

This turn to “altgenres” is why Netflix was able to transition from sharing other companies’ content to mostly producing their own, original video: they have a fine-grained sense of who wants to watch what, how much they want, and when they want it. It doesn’t matter if The Floor is Lava and Marriage or Mortgage aren’t any good. It doesn’t matter that Netflix spent a fraction of what traditional studios do on advertising or producing these shows. Netflix knew that people would watch them, so they made them. This is good in some ways (people get what they want) and nefarious in others (crowd preferences influence individuals more than individual preferences influence crowds; a whole team of people are staking much of their unique, precious human lives on producing The Floor is Lava).

But Netflix, at least, has competitors. Amazon, Hulu, HBO, Disney+ and the dozen other streaming platforms that probably launched as I type this sentence can do everything that Netflix does, too. The only competitor Goodreads had was Amazon.1 That’s why Amazon bought Goodreads in the first place. They were buying a data set and the tools to gather and refine that data. They have the world’s most sophisticated consumer data index guiding their decisions.

This is useful information if you’re one of the world’s largest publishers, like Amazon. This is even more useful if you’re also the world’s biggest seller of competitor’s books—like Amazon. They know how to make their own books and how to sell everybody else’s books. It’s as if Netflix collected all of their own user viewing data, plus everybody else’s, and they don’t have to share it. Amazon knows more about the competition than the competition itself. They know all the weird stuff: do senatorial memoirs perform better than congressional memoirs? Does proximity to Drain, Oregon correlate with a taste for mermaid erotica? Are women named Maude more interested in historical fiction with strong undercurrents of Catalonian nationalism? Amazon knows, because Goodreads tells them. And they’re not sharing.

So when authors face down a Goodreads review extortion and ask if star ratings matter, the honest answer is: we don’t know. The short answer is: probably.

Publishers and writers with a lot of experience marketing on Goodreads are convinced that the site’s algorithms often weight search results and recommendations towards new, popular, and well-rated books. The fact that Goodreads searches are so slow and inexact, often going out of their way to shove unrelated books above the closest results, is one pretty obvious indicator. So is the default sorting of user reviews, which favors reviews with lots of likes and comments.

None of this means Goodreads is deliberately trying to suppress unpopular or poorly-rated books. The platform’s code is meant to nudge people towards things they’re likely to enjoy. People enjoy good, new, popular books. Goodreads only knows what’s good and popular with the data it has: user reviews, tags, and ratings. That a flood of negative bot-reviews are easy to spot and disregard is besides the point: the software only sees data.

So when authors ask if star ratings matter, the answer is: yes, obviously. We don’t know how much they matter, but they clearly have a role to play. In the absence of public data, it’s hard to say if the cost of fake-review attacks is higher than the cost of extortion. It might even be good business to buy access to their bots for positive reviews and juice your book’s Goodreads numbers.

The real question, then, is: what can Goodreads do about this? Extortion, after all, is illegal. It’s also a violation of the terms of service. They have an obligation to act. But have you ever been to Goodreads? The site has barely updated its user interface in over a decade. The Android version of the Goodreads app is still missing key features. Goodreads itself has stopped promoting most of its key features. Most relevantly, Goodreads barely moderates reviews and ratings. Books that aren’t even commercially available can be reviewed by anybody—upcoming books by controversial authors are regularly swarmed with bad reviews, just as celebrity’s books are usually swaddled in praise as soon as the book’s page appears. Goodreads takes ages to respond to flagged reviews.

While they wait, authors often invoke one of Book Twitter’s grimmer rituals: pleading for friends and followers to balance out bad fake reviews with good fake reviews until the problem is solved. You’d think a company that relies on data would be more proactive in weeding out any fake data that threatens the integrity of their product. I’m sure they try.

The scale of the problem is probably just too big for individual moderators. Goodreads has two billion books listed and 120 million users. How do you moderate 120 million of anybody? How do you monitor two billion of anything? The problem won’t go away unless Goodreads makes changes to its foundation. And this is a company that hasn’t changed its fonts in a decade.

These extortion scams are horrible for the authors who face them. As I’ve tried to show, there are real consequences to these bot attacks, even if the scale of hurt is hard to measure. But these scams are only a side effect of the bigger problems with the world’s only social media platform for books.

Goodreads is an Amazon vassal fueled by clandestine, data-driven popularity contests, full of lying robots and influencers who review books with reaction GIFs, all of it painted in the worst shade of beige and duct-taped together with code from the second Bush administration. They have captured a substantial portion of the world’s enthusiasm for books and turned it into free labor harnessed for their own profit.

Can Goodreads be saved? The better question is: should it be saved? To be honest, I’m not sure. I’ve been a daily user of the site for close to a decade, though I only tried reviewing, tagging, liking, sharing, and contributing to it for a few months before I gave it up as pointless. As a database of almost every book you would ever want to read, it has real value. Some its reviewers are the most insightful people writing about literature today. (Read Glenn.) But I’m not sure if those goods outweigh the dangers of playing into Amazon’s bid to further reshape publishing for its own profit or contributing to the ecosystem that encourages review-bot extortion.

What you or I think doesn’t really matter, though. As Prateek Agarwal points out, Goodreads has an entrenched advantage among users and search results, and unlimited Amazon money to protect it from losing its perch. Like Facebook, Amazon, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube, and all the rest, it’s easier to imagine the end of Goodreads completely than it is to imagine competition and social pressure remaking it into a saner, healthier, less exploitative place. The current model just makes too much money to give up.

The short-term response, then—the one we have to live with for now—is the same for Goodreads as it is for most other platforms.

First, limit your usage and vigorously question every step of your participation in the symbolic economy of stars, likes, and comments. Strictly speaking, you don’t even have to rate a book on Goodreads to review it. The more you can make your role on the site one of words and not data, the less firepower you give to Amazon’s analytics team. This also has the salutary effect of forcing people to read you, rather than look at stars, thumbs-up, and other baubles.2 Assume nothing from star ratings and algorithmic suggestion boxes. They shape you more than you shape them. It’s one thing to help indie authors and small presses with your clicks, but you don’t have to donate your labor to help George R.R. Martin or Sally Rooney earn back their advance.

Second, keep a healthy book-life far from Goodreads, circulating among people you respect and admire. Read book sections in newspapers, read book reviews, talk to booksellers, go to libraries, get catalogs from cool indie publishers—do all the things literary people did for centuries before social media insinuated itself between every person, place, and thing. Find experts with sensitive, distinguished tastes that make their suggestions worthwhile.

Third, DON’T BUY BOOKS ON AMAZON.

Finally, and in the name of all that is good and literary, never, ever pay Goodreads review scammers or give them more than two neurons’ worth of thought.

A quick procedural note for this newsletter:

Over the summer, I had enough time to read and write enough to maintain a weekly publishing schedule for Bibliophilia. Now that the school year has started up again, I have to slow that down to every other weekend. I like to take my time with these posts and would hate to rush my essays between grading and lesson planning.

For the time being, then, you can expect a new Bibliophilia post every other Sunday morning. Happy reading!

Did you know your device’s Kindle ebook app tracks your reading?

Why else do you think Facebook made those “emotion react” buttons? It pays to know the difference between a laugh-like and a hate-like.