The Lost Book of Archimedes

How a letter from Archimedes survived the collapse of several empires, fire, mold, forgery, and literal erasure

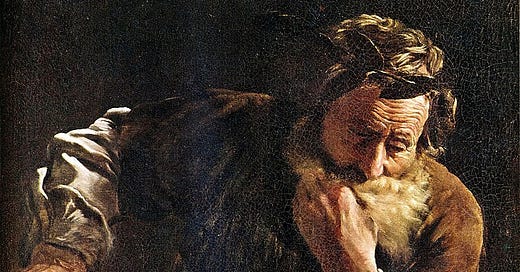

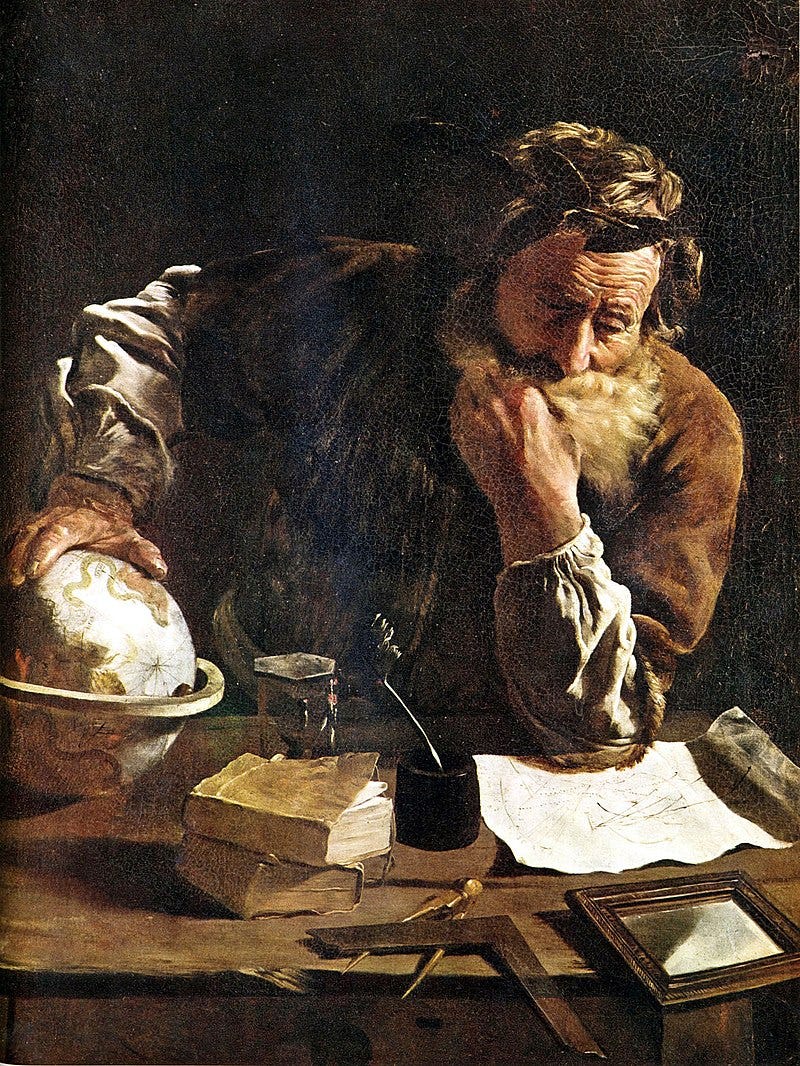

Some time before the Second Punic War, Archimedes of Syracuse (d. 212 BC) wrote a letter to a colleague. He had been fiddling with geometry, as always, scratching forms and figures onto wet sand (the blackboards of their day) finding a way to calculate the area of parabolas and spheres through an infinite regression of linear figures approximating the curved figure’s shape--the same method he had already used to demonstrate that the ratio of a circle’s circumference to its diameter is less than 227 but greater than 22371. Knowing how much his recipient delighted in geometry specifically and new discoveries in general, Archimedes wrote (or dictated) a letter that began:1

Archimedes to Eratosthenes: greetings! Since I know you are diligent, an excellent teacher of philosophy, and greatly interested in any mathematical investigation that may come your way, I thought it might be appropriate to write down and set forth for you a certain special method...I presume there will be some among the present as well as future generations who by means of the method here explained will be enabled to find other theorems which have not yet fallen to our share.

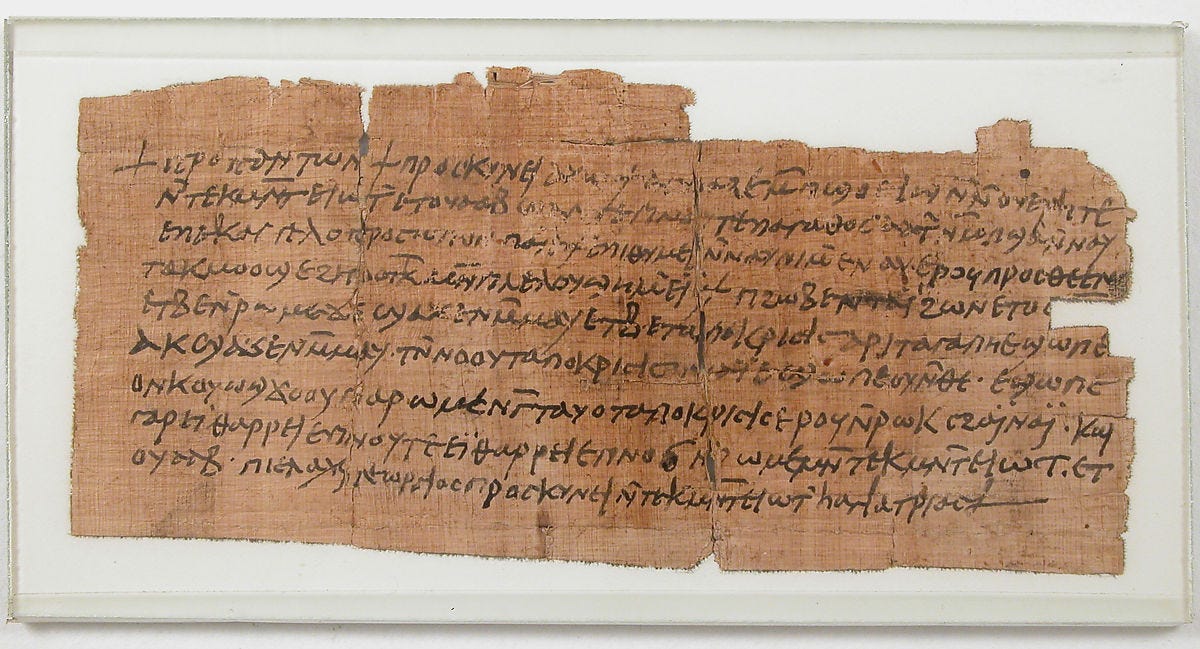

The letter would have been written on a roll of papyrus with a reed pen in dense columns of spaceless, capitalized Greek interspersed with diagrams copied from the sandpits. After it was finished, he sealed the letter with wax and entrusted it to the next outgoing ship to Alexandria.

If Archimedes wanted to spread and preserve his discovery, then he picked the right person in the right place: Eratosthenes was a member of the Library of Alexandria, one of the few places that systematically stored, copied, and spread knowledge in the ancient world, and by far its largest. Galen said the Library was so eager for books that by Eratosthenes’s time, the Pharaoh had empowered his agents to seize any unknown books they found among visitors and turn them over to the Library, which would make a copy, give that copy to the owner, and keep the original. Others, like Archimedes, mailed their books to Alexandria with the express purpose of preserving it and raising its chances of its contents surviving into the future.

At first, the plan worked: two and a half centuries after Archimedes died in the Siege of Syracuse, Hero of Alexandria was able to retrieve the letter to Eratosthenes and use it in his own work. But then we hear nothing of the letter or its contents for five hundred years, when Eutocius of Ascalon was compiling the remaining works of Archimedes, complaining bitterly of how few had survived. It’s remarkable that the letter, or any Archimedes, had survived at all.

While Archimedes the man had long since attained a reputation as a kind of Classical mad scientist who built death rays and mega-catapults, ran naked through the streets shouting Eureka! after he’d solved a problem in his bath, and died while practicing geometrical proofs during the sack of Syracuse,2 his actual writings weren’t especially popular with scribes and readers. Math and science writing ages poorly, especially--and ironically--as it becomes canonical, its key findings repeated in all books that build on it. (How many biologists today need to consult On the Origin of Species?) Archimedes’s Classical Doric dialect also made his works hard to read for 6th century Koine-speakers like Eutocius. And Alexandria’s Great Library fell apart over the centuries, suffering regularly from fires, earthquakes, and invasions. Whatever books survived were scattered far away, and rarely lasted long. Papyrus paper, like the plant it came from, was native to Egypt and thrived in its dry, stable climate; taken to the north, with its seasons, increased rainfall, and humidity, most of it disintegrated into dust within decades, and copying into parchment was slow and expensive.

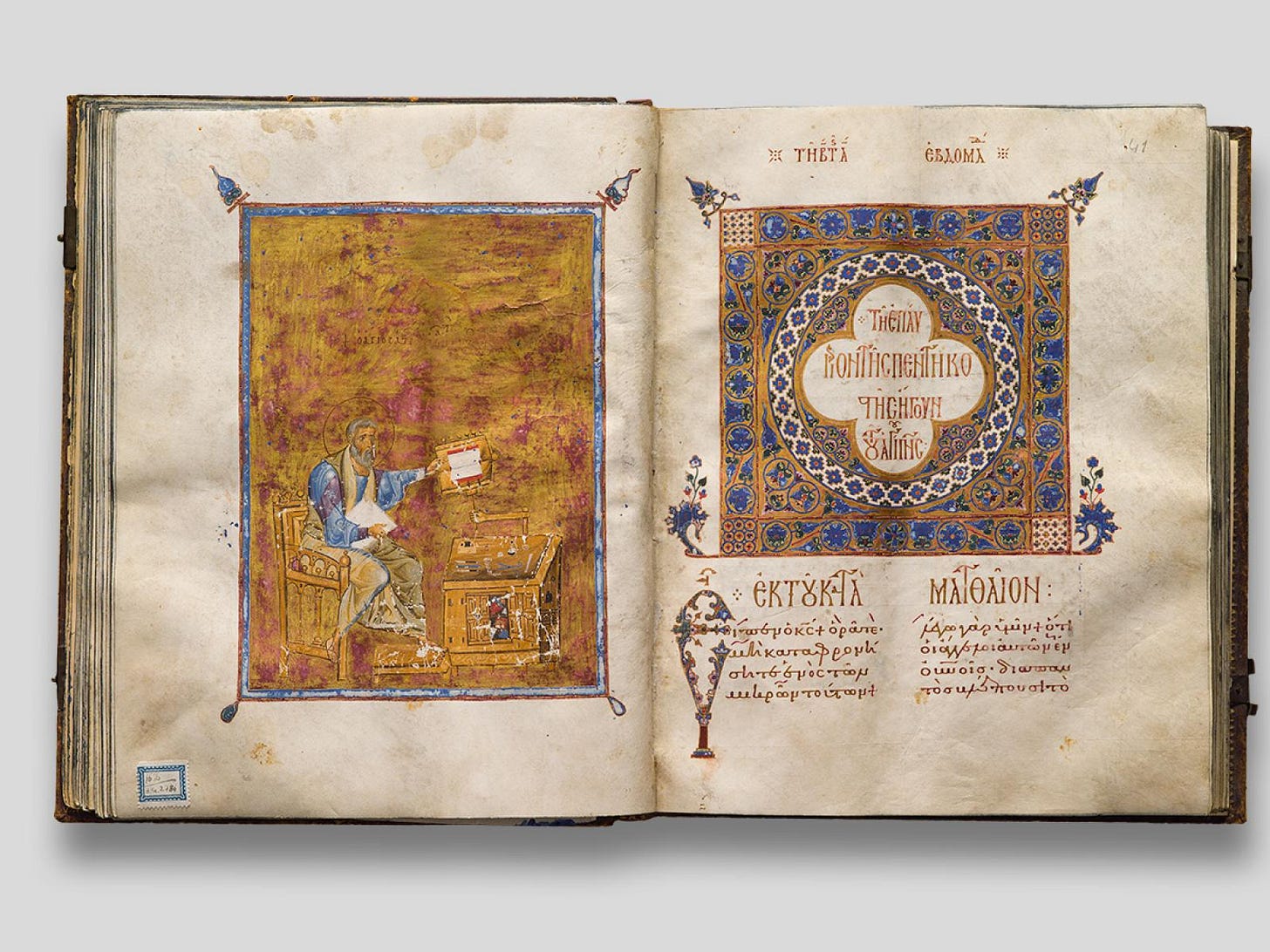

Exactly when the need to recopy ancient literature was greatest, though, the Roman Empire was going through its conversion to Christianity. Since at least Edward Gibbon, the loss of so many books around this time has been chalked up to orgies of anti-pagan book burning, though the likely truth is more banal: Christian scribes simply didn’t have the time or interest for copying Alexandrian sex manuals or Roman orations. At least a few of them, though, found Archimedean math useful enough to copy: Eutocius’s collected Archimedes made it to Constantinople, and one of the chief architects of the Hagia Sophia was an expert on Archimedes. His work wasn’t popular--when is math ever popular?--but it was safely stored and copied when necessary. It even made the jump to miniscule writing (lower case, essentially) in the 9th century, as the Byzantines were throwing out or recycling any of the old all-caps majuscule books not important enough to copy. A thousand years after his death, Archimedes still had fans, his letter to Eratosthenes still read.

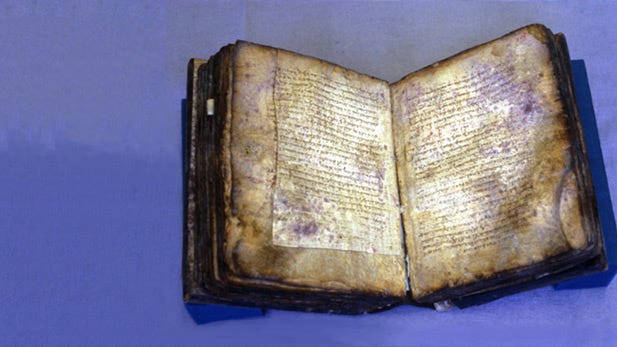

Some time around AD 950, though, the letter was copied for the last time. A Byzantine scribe sat down with a book--or books--of Archimedes,and began to copy it onto parchment quires. The finished copy seems to have sat on a shelf for two hundred years, not much used but at least kept in a safe place.

In 1204 AD, though, Constantinople was not a safe place: it was sacked by soldiers of the Fourth Crusade, who ran off with treasures, captives, and books--including Archimedes. Only three collections of Archimedes survived: two went home to Italy with the victorious soldiers, where they were translated into Latin and became cornerstones of Renaissance engineering and the Scientific Revolution, constituting everything we knew about Archimedean mathematics for seven centuries. The letter to Eratosthenes, however, wasn’t in Italy or Catholic Europe at all. Nobody even knew there was more Archimedes to find. The third book of Archimedes had been erased.

Somewhere in a Palestinian monastery a few years after the sacking of Constantinople, somebody had taken this book, removed the cover, cut the bindings of the folios, cut those folios in half, and laid the individual leaves of the book flat. He applied some kind of acid to the page which dissolved the ink, then scrubbed away with a pumice stone the last copy of Archimedes’s letter to Eratosthenes and its unique mathematical proofs. After the blank sheets dried, they were turned on their side and folded again, making a stack of pages twice as thick and half the size of the original, ready to become a new book. In 1229, a scribe grabbed these pages, set them on his writing stand, and over the faint remains of Archimedes wrote a book of prayers.

This was a common practice, rooted in the scarcity and expense of parchment. As a writing surface,treated animal skins were durable, light, and smooth, but also expensive: a three-hundred page book like the one our scribe was making required dozens of animal skins. Because parchment was so much sturdier than the ink written on it, though, it was possible to remove the ink but save the parchment, recycling it into fresh material for a new book.. A palimpsest, as these recycled books are called, retains only faint traces of the original text.

And so, while Archimedes was cited and celebrated by Brunelleschi, Leonardo, and Galileo and copies of his works in Latin were treasured and reprinted, Orthodox monks were dripping candle wax over his lost works as they looked for the appropriate prayer for blessing an Easter loaf. Whether the monks noticed anything about the faint text running in lines perpendicular to the prayers and disappearing into the page gutters we do not know. But they kept the book for nearly seven hundred years.

It took a secular Greek professor in 1899 to notice the book hidden within the book while cataloguing the library of the Patriarchate of Constantinople, where the Archimedes palimpsest had made its way towards sometime in the early 19th century. He noted that the prayer book was a palimpsest with some ancient Greek mathematics written on it, transcribed a bit of it, and moved on. The Danish historian Johan Heiburg saw this catalogue and immediately recognized the ancient Greek quote as Archimedes. He went to Istanbul in 1906 and, with the Patriarchate’s permission, took out this crumbling, seven hundred year-old book, turned it sideways, and with a magnifying glass, began to read.

Sure enough, the book was full of Archimedes: not just familiar works like Balancing Planes, Sphere and Cylinder, Measurement of the Circle, Spiral Lines, and On Floating Bodies, but also two entirely new works: a combinatorial puzzle called the Stomachache and the letter to Eratosthenes. They were fragmentary, with many gaps and sections where the text disappeared into the gutter, and the whole text was completely shuffled by the palimpsesting process, but Heiberg was able to make out enough to understand its significance: here were completely unknown works of Archimedes that suggested the ancient Greeks knew far more about combinatorics and infinitesimals than previously thought. Heiberg recorded as much as he could, photographed the whole thing, and published his findings in 1910, with the understanding that further research into the manuscript would produce better, less fragmentary readings and more knowledge.

But history was not done playing with Archimedes. Heiberg was fortunate to visit Istanbul when he did; only a few years later, the Ottoman Empire was engaged in a series of wars, from rebellions in its Balkan provinces to World War I to the Greco-Turkish War and related Turkish War of Independence, culminating in the fall of the Ottomans, the genocidal ethnic cleansing of Greeks, Armenians, and Assyrians. As part of the expulsion of Greeks from Turkey, the Patriarchate of Constantinople moved most of its books to Athens throughout the 1920s and 30s, and one of those books should have been the Archimedes Codex--but it never made it. Once again, Constantinople had fallen and Archimedes had disappeared.

It emerged in Paris in the 1930s, in the inventory of a rare book dealer called Salomon Guerson. How he attained the book is unclear, though he was probably at least a few degrees separated from the theft and looting that brought so many of the Patriarchate’s rare manuscripts into private collections around the world. We know from his letters that he tried selling it to institutes across Europe and North America, but with no luck. We also know that he didn’t have it when he fled Vichy Paris in 1943 (Guerson was Jewish), and in all likelihood gave or sold it to Marie Louis Sirvieix of the French Resistance. Either Guerson, Sirvieix, or both had taken the extraordinary step of trying to make the Codex more marketable to buyers by painting over several pages with tacky forgeries of Orthodox manuscript illustrations. This didn’t get the whole book sold, but they managed to cut out and sell a few as loose-leaf illustrations. The rest of the mangled book sat in Sirvieix’s damp, moldy basement for decades.

Perhaps sensing that the man was a hero to his country but a scoundrel to academics and booklovers, Sirvieix’s descendents waited until 1999 to finally put the Archimedes Codex up for auction.The Patriarchate of Constantinople, understandably, sued the auction house and promised to sue whoever bought their stolen property (they lost). A bidding war quickly developed between Greece’s Ministry of Culture and an anonymous American billionaire whose agent was only permitted to say was not Bill Gates; the billionaire won, paying 2.2 million dollars. Like so many other rich collectors, the anonymous Scrooge could have taken his treasure and disappeared, continuing a very long, strange journey for the Archimedes Palimpsest, but for once Archimedes had a lucky break: the new owner was keen to lend it out to an institute with the expertise and technology to read it, and he was willing to foot the bill himself. There was nothing for him to display, after all, besides a moldy, torn, prayer book filled with chintzy forgeries.

The Palimpsest wound up in Baltimore, where it was carefully taken apart and scanned six ways to Sunday and close-read as no text has ever been close-read before, using microscopy and spectronomy to trace the text of Archimedes text by the nanometer. And there, in these laboratories, displayed on high definition monitors, was Archimedes, some 23 centuries after writing his letter, which had crossed oceans, survived empires, fire, mold, and erasure itself, telling Eratosthenes about the most remarkable theorems he had just scratched out in the sand.

Sources & Further Reading

Unless otherwise attributed here, the general outline of the Archimedes Codex and the letter to Eratosthenes (and translation) are from The Archimedes Codex: How a Medieval Prayer Book Is Revealing the True Genius of Antiquity’s Greatest Scientist by Reviel Netz and William Noel, who were part of the team that restored the Codex. I’ve drawn especially from the chapters “The Great Race” and “The Great Race, Part II,” but any readers more curious about Archimedes himself, his mathematics, codicology, and how they managed to restore the Codex should read this book.

I also checked my information against parts of Alan W. Hirshfeld’s Eureka Man: The Life and Legacy of Archimedes.

Translation by Reviel Netz. The details of the following story are taken largely from The Archimedes Codex by Netz & Noel. See my sources list at the end for more detail.

All of these are false. The convex mirror “death ray” was a Byzantine fiction and has never been replicated; the Eureka! moment with the “discovery” of displacement would have been trivial for the man who wrote the much more sophisticated On Floating Bodies; his famous last words, noli turbare circulos meos, (do not disturb my circles) smack of myth. He was also not the inventor the water screw, as the Romans seemed to think—the Egyptians had already been using them for centuries.