There's this old canard you hear sometimes that computer bugs used to be real, squirming, chitin-coated bugs. The story, often told by the computer scientist Grace Hopper, was that on September 9th, 1947, her team of engineers really did find a moth inside their computer, disrupting the electronic circuitry. One of the engineers cheekily pasted the dead creature in the logbook, writing: "First actual case of bug being found."

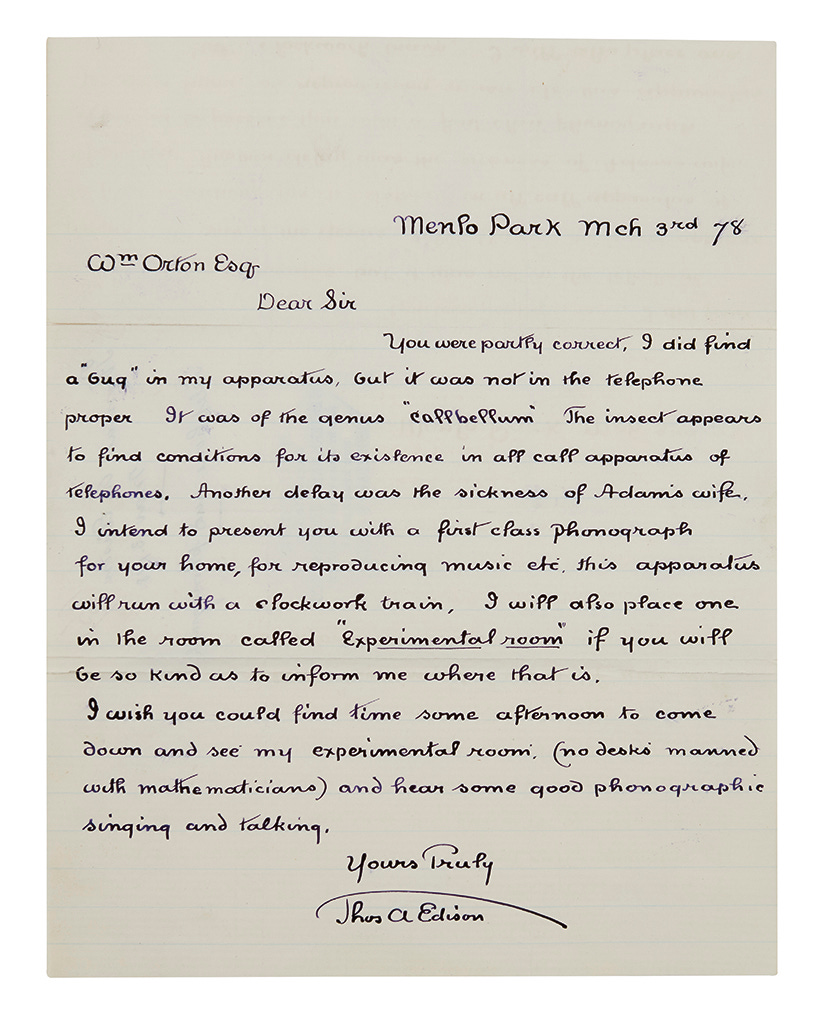

But this was a joke, not a discovery. "Bug" was already in use to describe glitches in electronic machinery, going back at least to an 1878 letter from Thomas Edison. Take a look at the letter, written out by Edison himself in his own hand.

Look at that script! I look at a fair deal of handwriting for this blog, and I’d never seen anything like this. I started poking around, and found out that Edison's script really was unique in its structure, for uniquely Edisonian reasons. But I also found out, thanks to this doorstopper article by David Kaminski, that Edison's very weird script has a crucial link to the history of American libraries, and fits into a much wider history of how writing in the 19th century had to be adapted to the needs of the modern bureaucracy.

Telegrapher's Hand & Edison’s Idiograph

When Thomas Alva Edison was attending school in the 1850s, the dominant style of handwriting among educated Americans was the so-called Spencerian script. The author and calligrapher Platt Rogers Spencer had started selling his writing handbooks in 1848, promoting his style as freer, less cramped, and more readable than the "copperplate," or "round"" hand that had ruled American letters. Both styles are quite ornate: copperplate is best-known as the style America’s founding documents were written in, while a Spencerian script was used for the Coca-Cola logo.

The problem was, Spencerian script's focus on expression and beauty was good for writing serious business letters or florid love poems, but it was a terrible fit for the cramped, boxy blocks of telegraph forms. In fact, in Kaminski's telling, there wasn't any formal, standardized way to write letters in early telegraphy, leading to a great deal of confusion and inefficiency. The writing of letters was up to the telegrapher, and before long you had all kinds of "Telegraph" hands showing up. One of the most innovative and efficiency-minded of these telegraphers was a teenaged Edison, whose first job was transcribing telegraph messages.

Edison told later biographers that at the time, he thought a great deal about how to write faster, clearer letters, experimenting constantly with his letter forms. Kaminski identifies a few early samples from the 1860s and 1870s. Already, they are far from the standard, Spencerian style: individual letters instead of joined, vertical or backward-slanting strokes instead of forward, and with all kinds of swooshing, kinetic strokes meant to reduce the amount of effort needed to make a distinctive letter. It looked weird, but it was also fast and clear.

By the 1878 letter above, written at the age of thirty, Edison had created a mature style, one that he stuck to for most of the rest of his life. He swore by its effectiveness. An acquaintance, quoted by Kaminski, once observed him writing:

When he writes slowly and with care—from fifteen to twenty-five words a minute—Mr. Edison's handwriting is phenomenally clear and beautiful, resembling copperplate printing; not in a flowing, but in a cramped hand, the letters often being separated as in print. When he rises to forty words a minute, the writing is still more cramped and less beautiful, though yet legible; with forty-nine words a minute, his writing is quite illegible.

Given how strikingly Edisonian the whole story is, with themes of innovation, efficiency, and experiment, it's surprising that Edison's handwriting isn't a bigger part of the whole Wizard of Menlo Park mythos. But at least one other ultra-organizer was paying attention.

“Lord Palmerston is an enemy to the up-strokes being too thin”

Telegraphers weren't the only ones struggling with the problems of running massive, modern bureaucracies in a pre-typewriter age. Take Lord Palmerston,1 who pretty much controlled British foreign policy at the peak of its power in the middle of the 19th century. It took a lot of paperwork to manage the affairs of six continents, most of it handwritten by agents of the empire.

At that scale, any graphological problems in accuracy or speed can be compounded at massive scale—if you've ever had to ask somebody to clarify their last email before you can proceed, imagine having to wait six months for their reply to reach you from Hyderabad and you can imagine the kinds of problems Palmerston was regularly facing.

For that reason, Palmerston had what one historian called an "obsessive concern with the quality of handwriting produced by FO clerks and consuls... Numerous notes in his own hand inveigh against illegible handwriting, weak syntax, sloppy style and deficient punctuation skills, as well as the poor quality of pen-nibs and the paleness of ink used by his underlings." He complained that reading one clerk's writing "is like running Pen Knives into ones Eyes."

Others remarked about Palmerston’s views on good handwriting. On page 40 of Handwriting of the Twentieth Century, Rosemary Sassoon quotes this gloriously-phrased letter from Palmerston's wife:

Lord Palmerston is an Enemy to the upstrokes being two (sic) thin and contrasting too much with the downstrokes. He has therefore scratched over with his Pen two of your lines to shew that all the letters should be rounded and clear—and the Upstrokes sufficiently dark not to deceive the Eye, otherwise the letters seem only half formed.

As a result of Palmerston's obsessive micromanaging over penmanship, there developed a kind of house style at the Foreign Office known as either the civil service style, or "round hand" (though it is very different from the 17th century clerk script usually known by that name).

As a slanting, cursive script, Palmerston's civil service style bears no direct resemblance to Edison's handwriting or the wider world of vertical, unjoined telegraph writing. But the idea of reforming handwriting to be more efficient, clear, and standardized traveled across the Atlantic.

The Library Hand

In 1885, the American Library Association had a meeting to discuss the standardization of handwriting in American library catalogs. America's librarians were interested in reforming their catalogs for the same reason that Palmerston was: sloppy penmanship slows down the transmission of information, and even threatens lost connections and dead ends. If the United States ever wanted to create a true science of librarianship like the Europeans were doing, it would be necessary to improve the quality and consistency of its catalogs, starting with the way they were written.

And so the ALA met to discuss creating an official librarian's hand, to be taught and used by all ALA members.2 One style was the British round hand, still in use at the Foreign Office decades after Palmerston's death. But then a certain Mr. Nelson raised an interesting possibility:

I saw in a recent number of "Science," (Number for August 21 ; 6 : 46) in a sketch of T. A. Edison, the inventor, the statement that Edison had "experimented to devise the best style of penmanship for telegraph operators, selecting finally a slight back- hand, with regular round letters apart from each other, and not shaded, attaining himself by its means a speed of forty-five words a minute." He thought that this hand might prove suitable for cards, by reason of its clearness, and the speed claimed for it.

Melvil Dewey was present at the conference. The second edition of his Decimal System for library classification had just come out, and he was only a few years away from establishing America’s first university library program. He had spent a lot of time thinking about how to better sort, store, and access information.

There was a lot of work to be done. At the time, there was no consistent practice among American librarians at all. Every institution had its particular methods for ordering and cataloging information, and these methods often changed over decades as new generations of librarians reorganized, recataloged, and replaced holdings in inconsistent ways. Like Palmerston in the FO, Dewey realized that handwriting was a crucial, neglected component of modern bureaucracy, and that a lot of potential gains in efficiency and stability were being left on the table because older librarians didn’t like to change their ingrained habits.

So, following Nelson’s proposal, in 1886 Dewey sent a letter to Thomas Edison, asking about his penmanship.

Edison was out of town. His secretary responded by sending Dewey a collection of samples from his master's hand. As far as we know, that was the last communication Dewey had with Edison over handwriting. Less than a year later, Dewey was publishing the first versions of the library hand.

Few of Edison's stylistic peculiarities made it into the ALA's suggestions, though the basic idea was there: vertical writing, mostly unjoined, with highly regular spacing. By 1887, Dewey and his colleagues had drafted the first edition of library hand based on these principles.

Despite the efforts of Dewey and the ALA, there never was a single, universal library hand. Kaminski finds new editions of the script published in 1898, 1904, 1912, and 1916. Variant forms, including cursive forms for those librarians who couldn't commit to the barbarism of unjoined letters, were grudgingly allowed. The system was officially taught to all librarians for many decades, and was considered an essential skill for the profession.

Even as the teaching of library hand declined in favor of typewriters and photocopiers in the 1950s, Dewey’s script survived, and covertly thrived. The idea of library hand had permeated the field so thoroughly, that librarians didn't even know that they were using it. Kaminski:

Today, those who have worked in libraries without a full understanding of library hand will often still write in a way that they see on the books, folders, materials around them. Numerous librarians and employees I have spoken to use printing, capitals, and a leftward slant with no knowledge that they are imitating library handwriting, such as in these file folders and microfilm labels from 2015. These employees, as young as their twenties and thirties, continue in the profession and promulgate the style that the Cooperation Committee and Melvil Dewey set forth more than 125 years previously.

We can see here the full life-cycle of an innovation: from curio to novelty, cutting-edge to institutionalized, and finally so ingrained that nobody even knows it had to be thought up in the first place. And it all comes down to Thomas Edison’s zeal for efficiency. Well, that and Lord Palmerston’s eternal enmity towards the up-strokes being too thin.

I have never seen or heard anybody refer to Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston referred to as anything other than his title, so I’m sticking with Lord Palmerston here.

The possibility of using typewriters, a new but rising technology at the time, was also discussed. For reasons that aren’t clear from the transcripts Kaminski quotes, the ALA decided to table the discussion and focus on scripts.