Links for February (And January)

Weird maps, talking submarine cables, yelling about English majors

Here are some of the best book-adjacent things I read in February. And also January, since I didn’t make a link round-up for that month thanks to a bout of depression. Thankfully, that seems to have passed. Now, the links, and this month’s visual theme:

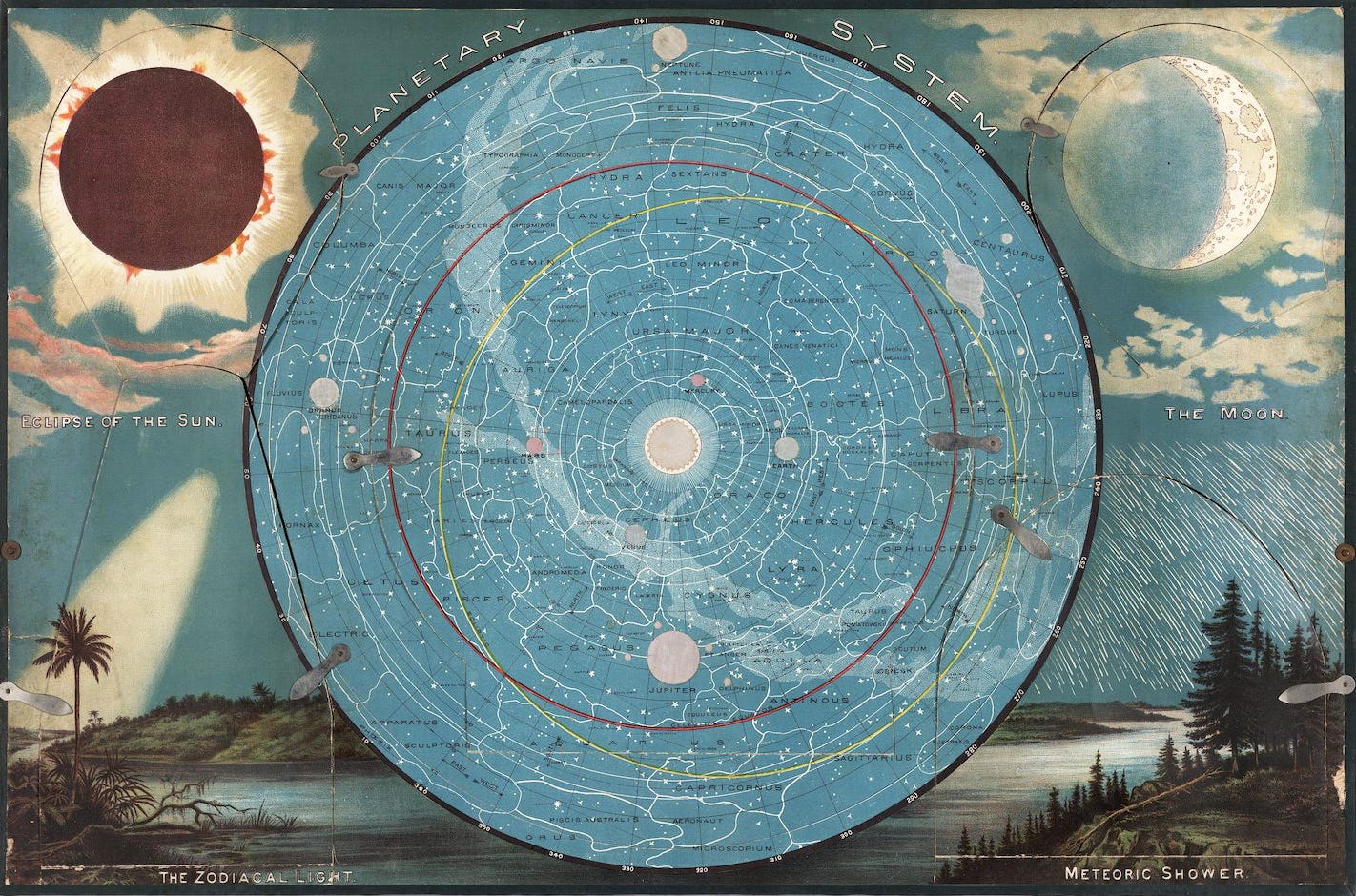

“Is there a cost to making a map more charming than true?”

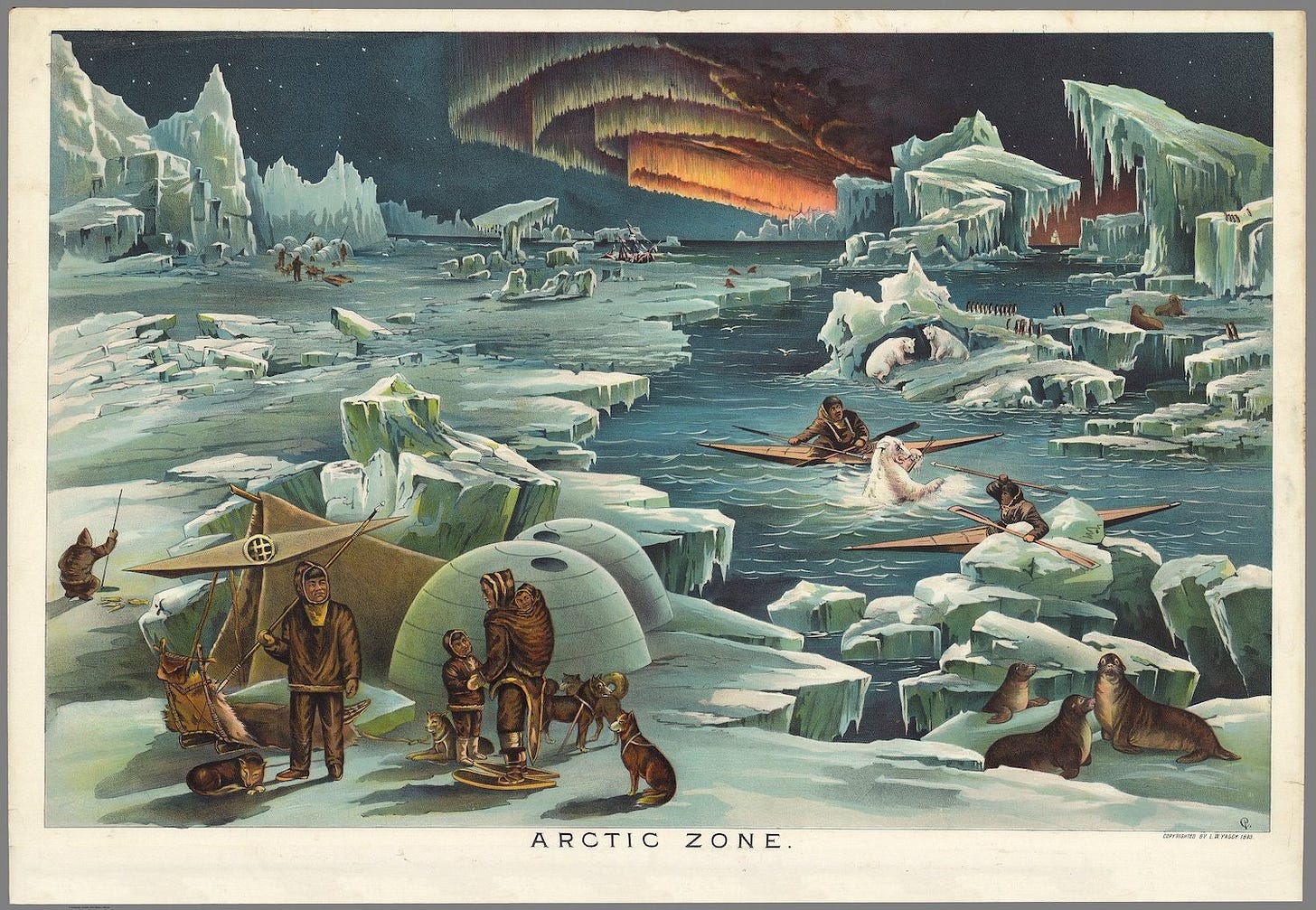

Sasha Archibald asks this question in The Public Domain Review while considering L.W. Yaggy’s 1887 Geographical Maps and Charts. Yaggy’s maps of flora, fauna, geology, astronomy, and ecology, published for classroom use in 1887, were marvels of mapmaking:

Some of “Yaggy’s maps”, as they were usually called, are straightforward two-dimensional posters, but others feature elaborate cutaways and intricate layers. “Physical Geography”, for instance, presents as a bucolic orb of rivers and fields, with an erupting volcano in the corner. By adjusting riveted metal tabs, this scene falls away, and a new view is revealed underneath, showing all variety of subterranean human activity: Venetian grottoes; a cave in Kentucky; quartz, salt, and coal mines. Beneath this layer is another, with a diagram of the stratified ages of the earth in striped autumnal colors; and then, finally, the mass of land becomes a bustling aquarium, starring a one-eyed octopus and a fleet of pulsing jellyfish. The cutaways in Yaggy’s “Planetary System” map are even more complex. Seasons can be adjusted with a dial, and translucent linen inlays reveal the corresponding placement of constellations, which shine when backlit. There’s a cutaway showing the phases of a solar eclipse, and another with a view of the moon as seen by the world’s most powerful telescope. Every corner packs a surprise; the innermost layer, “Chart of the Heavens”, draws the nocturnal sky like a party, crowded with animals and gods.

Thankfully, we don’t have to rely on these as accurate models of the physical world, leaving us free to enjoy them like the gonzo prog-rock album covers that they should be (and could be, since they are public domain). I’ve scattered a few more of my favorites throughout the post.

Why Is It So Hard to Catch Your Own Typos?

Nick Stockton took this question up back in 2014 at Wired, but I’m only just getting around to it and am already thinking of ways to incorporate this in my writing instruction. The human brain—that magnificent, gooey lump of neurons that gave the world languages, abstract representation, and some really sick tools for hunting woolly mammoths or nuclear submarines—is a bit overfitted to the finicky, laborious task of copyediting. It takes shortcuts whenever it can, to conserve energy for whenever the next sabertooth emerges from the grass, so when you try to force it to look over squiggly, ant-like lines of text, it starts skipping and skimming along. We’ve already done this, chief, your brain says. Even when you force yourself to reread your long paragraph about, say, Thomas Edison’s handwriting, your mind is taking shortcuts, scooping up big gobs of text without scrutinizing the little letterforms. And so, you miss a bunch of typos. Stockton’s advice? Trick your brain into thinking it’s looking at something new by changing fonts, colors, word processor, or even the place where you read & write. I already do several of these, wihch must be why I make so few tyops.

The Books That Made the Enlightenment

At The Critic, David Wootton has a very interesting review of a very interesting new book. The Books that Made the European Enlightenment: A History in 12 Case Studies is historian Gary Kates’s attempt to explain the Enlightenment through a careful look at the drafting, editing, publishing, and distribution of a dozen representative books, like Montesquieu’s The Spirit of the Laws or Voltaire’s Letters Concerning the English Nation. The book argues that, as Wootton writes, “the Enlightenment can be thought of as a programme of reading a set of books that writers and readers had in common.” The philosophes were continually reacting at, responding to, and marking up each others’ works, and this was how much of their work was actually done. The national sport of the Republic of Letters, apparently, was intellectual ping-pong. I’ll be reading the book soon, hopefully.

“A frightful hobgoblin stalks throughout Europe”

From the context of his review of China Miéville’s A Spectre, Haunting, James Robbins of The New Republic clearly wants you to find the quote above, from Helen Macfarlane’s 1851 translation of The Communist Manifesto (the first one in English) laughably inferior to the later, more famous translation Miéville uses for his book. The problem is, I quite like Macfarlane’s Englishing. For one thing, it’s hilarious. For another, it gets quite closer to the spirit of revolutionary communism in the real world. Specters are the cool guys of ghost vocabulary, and it’s also the name of the bad guys in the James Bond series, so you can see why communists would prefer it. But regardless of where you fall on the issue of state-sponsored mass-murder, there’s no doubt that real communists have always been blundering, stumbling dorks. In that sense, hobgoblin seems like a perfectly cromulent word to describe communism. Anyway, this is a book blog, so here’s a bit of useful literary history:

In a way, what China Miéville has written is an inadvertent tribute to the smallness of The Communist Manifesto. Its influence was “utterly epochal,” yes, but that came much later—especially when the European socialist parties came to the fore in the early 1900s, especially after the formation of the Soviet Union. In its own time, Marx and Engels’s program was hardly read beyond the tiny correspondence committees of radical workers and intellectuals already well versed in the emerging socialism of Proudhon, Fourier, and Owen. If one were to make an educated guess, between 1848 and the Paris Commune of 1871, probably not more than a few thousand people had ever heard about this swingeing1 little book.

The Autobiography of the Submarine Telegraph Cable, Written by Its Self

In the midst of Ceridwen Dovey’s not-especially-interesting article on the history of objects as narrators, my patience was finally rewarded with an excerpt from the 1859 The story of my life: by the submarine telegraph. It was probably written by one Charles West, but it can’t be proved. What can be proved beyond a doubt, though, is that this story slaps. Here’s a taste:

I am but in my childhood yet, although I am several years older than the world has been led to believe my age to be. Young as I am, however, few have undergone more suffering, and been subjected to greater cruelties during a long life, than I have in my short career. My severed and scattered limbs, now lying at the bottom of the ocean, in various parts of the globe, bear ample testimony to my ill usage.

I do not mean to accuse any of the individuals by whom I have been subjected to this torture, of any wilful or intended cruelty; it is the result, rather, of their not properly understanding me, and the peculiar requirements to fit me for my ocean bed…I am induced to publish [my narrative]…solely with the view of placing myself in my right position with the public, and of inspiring them with the same conviction that I have myself, of my being able…to bring, by my extraordinary power, distance countries, separated from each other by the ocean, into close and immediate intercommunication.

Making Parchment For Fun & Profit

“On Skin, How a Page is Made From It,” by Conrad Mure (c. AD 1270):

The skin of a calf is flayed and deposited in water.

Lime is added, to gnaw away everything rough,

To clean it well, and to remove the hairs.

A circular frame is fashioned, on which the hide is stretched.

It is placed in the sun, so that moisture may be driven out.

Now comes a sharp knife; it rips out flesh and hairs;

It renders the skin fine and pleasing.

“The poem closes,” Bruce Holsinger notes, “with a moralizing couplet that plays on the commonplace medieval association of flesh and page: “Skin from flesh, flesh from skin removed: You, too, must withdraw your carnal lust from the flesh.” The rest of this excerpt from Holsinger’s book On Parchment is too rich an anecdote to quote further, and I don’t want to spoil too much of it because I only got halfway through it before stopping, because I already knew I was going to read the whole book eventually.

Two Views on the Death of the English Major

The lit’ry blogosphere is alight this week with Nathan Heller’s big New Yorker thing on the decline, in both prestige and in absolute numbers, of the English undergraduate degree in American universities. There’s plenty to agree with there (I was comforted, as a high school teacher, to learn that even Harvard undergrads are now so pickled in TikTok that they struggle to identify parts of speech in writing), and plenty to get frustrated with (even when the subject is ostensibly Arizona State University, the real subject still winds up being Ivy League schools, which represent a tiny fraction of college students, but a large portion of New Yorker readers and the entirety of New Yorker’s staff).

Mostly though, I found myself frustrated with Heller’s continued insistence that English majors are in decline because of larger disinvestments from government, universities, and other public institutions. Everybody knows that. The mistake Heller makes is to act as though the CIA no longer funding literary magazines is some kind of fall from grace when it’s just a regression to the mean. University programs dedicated to analyzing contemporary vernacular literature are only a century old, and for the first third of their existence, they were tiny and pathetic little corners of academia; then, flush with Cold War cash, they were big and brawny agents of democracy, enjoying prestige and popular support; and in the last third, they’ve been in a long decline as the big wave of money recedes. There’s nothing weird about Kids These Days not giving a shit about old poems; what was weird was how many kids in the 1960s and 1970s thought studying literature was an important, useful thing. That probably won’t come back, which is why I agree with John Guillory: manage the decline.

And that’s it for this week. Happy reading!

Not actually a typo; I learned a new word!